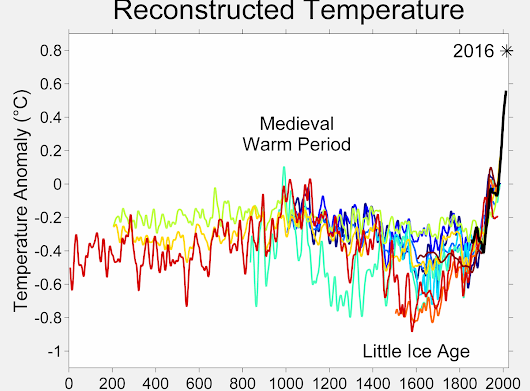

Long before the bitter cold winters and drenching rains of the early 14th century announced the end of the Medieval Warm Period (MWP), Europe had expanded dangerously close to the limits of its resources. Four centuries of unusually mild temperatures (the highest in 8,000 years), prompted the continent’s farmers to plant crops on vast quantities of land previously unsuitable for agriculture; the increased food supply in turn fueled a population explosion that tripled the number of people in medieval Europe.

Several causes have been proposed for climatic cooling: cyclical lows in solar radiation, heightened volcanic activity, changes in the ocean circulation, variations in Earth's orbit and axial tilt (orbital forcing), inherent variability in global climate, and decreases in the human population.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ztninkgZ0ws

Higher April to July mean temperatures prevailed in the first decade of the fourteenth century, during the late 1320s and early 1330s, the 1350s and the 1390s. Lower temperatures marked the mid-1290s, about 1313 to 1323, the late 1330s and 1340s, the mid-1360s to the mid-1370s and the 1380s. Additionally the reconstruction reveals periods of high and low inter-annual variability in the spring and early summer temperatures. Between 1315 and 1335 as well as 1360–1375 the year to year variability was especially high: jumps in growing season temperatures from one year to the next were frequently reaching 1.5°C. Phases of medium inter-annual variability marked 1290–1315, about 1405–1411 and the early 1420s. Finally, during the second half of the 1330s and in the 1340s, in the 1350s, around 1380 and in the 1410s spring and early summer temperatures were comparatively stable.

1384

During this summer there was so great a drought that streams and springs which normally gushed from the ground in ceaseless flow, and indeed, as seemed yet more remarkable, even the deepest wells, all dried up. The drought lasted until the Nativity of the Virgin [8 September, Old Style]; […]. In the course of the summer the larger cattle died in very great numbers through the shortage of water.

The reconstructed April–July mean temperatures 1256–1431, based on grain harvest dates (Pribyl et al., 2012). The grey error bars represent ±2 S.E. (RMSE) derived from the regression analysis during the 1768–1816 calibration period.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/enhanced/figures/doi/10.1002/wea.2317#figure-viewer-wea2317-fig-0003

The impact of weather induced harvest failure in the Middle Ages is dependent on population density, infrastructure and the transport network, the storage capacity for grain, the access to other resources, the integration in wider trade networks and the capacity of the authorities to organise relief measures.

High inter-annual variability of the growing season -temperature alone could cause severe problems for medieval agriculture, as could periods of cold springs and summers that were often coupled with raised precipitation levels. So during the cold and variable 1310s the worst famine of the last millennium in northwestern Europe occurred 1315–1317, caused by incessant rains. In England 10% of the population are estimated to have fallen victim to this famine. During the 1360s grain prices remained high, even though the population loss due to recurrent plague waves reached at least 30% and hence lowered the demand for grain. Again, weather was cold and variable and high rainfall levels interfered with agricultural production. During the warm springs and early summers of the 1330s and 1410s grain prices were stable and generally low.

Extreme weather as well as long term climatic change could also influence land use and settlement patterns. Climate change also constituted a factor in the desertion of villages during the later Middle Ages. It is likely that in England desertions also took place in villages, where an unfavourable combination of climate and soil conditions rendered agriculture more vulnerable.

Famine in medieval England

http://www.medievalists.net/2015/12/20/approaches-to-famine-in-medieval-england/

14th C end of the Medieval Warm Period (MWP)

Borehole inversions indicate a globally coherent pattern of cooling from the Medieval Warm Period to the Little Ice Age that is also documented in recent land and ocean proxy compilations. The ocean adjusts to surface temperature anomalies over time scales greater than 1000 years in the deep Pacific, which suggests that it too hosts signals related to Common Era changes in surface climate.

Little Ice Age

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oYdCE0SqrJM

1315-22 Wet summers, rinderpest, crop failure, famine, and decimation followed by the Great Pestilence and the Peasants' Revolt of 1381

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Ice_Age

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wea.2317/full

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_Warm_Period

https://www.thedailybeast.com/when-the-weather-went-all-medieval-climate-change-famine-and-mass-death