Birth, Marriage, Children, Life, Death ..

Burial ..

Birth, Marriage, Children, Life, Death

Birth, Marriage, Children, Life, Death

A History of Childbirth: Delivery - LiHo > .

Part 1, Conception: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_A8yK...

Part 1, Conception: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_A8yK...

Part 2, Pregnancy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s6zB8...

Part 3, Labor: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JhEi7...

Sources: Cassidy, Tina. Birth: the surprising history of how we are born; Thorndike Press, 2007.

A Day In the Life Living With the Plague > .

Pre-Modern Death in Childbirth

Pre-modern childbirth was more dangerous than it is in the most dangerous-to-birth-in countries today. Some evidence from New England suggests an average maternal mortality rate of 2.5%. That is, for every 1000 births, there would be 25 women who died. In countries with the maternal mortality closest to that, (calculated over multiple births) 1 in 6 childbearing woman will die from complications of childbearing; we can expect that the rate was similar in pre-modern times.

http://birthnerd.blogspot.ca/2011/07/pre-modern-death-in-childbirth.html .

https://www.tudorsociety.com/childbirth-in-medieval-and-tudor-times-by-sarah-bryson/ .

Medieval Lives - Birth, Marriage, Death (Series) - HuDa >> .

Pre-Modern Death in Childbirth

Pre-modern childbirth was more dangerous than it is in the most dangerous-to-birth-in countries today. Some evidence from New England suggests an average maternal mortality rate of 2.5%. That is, for every 1000 births, there would be 25 women who died. In countries with the maternal mortality closest to that, (calculated over multiple births) 1 in 6 childbearing woman will die from complications of childbearing; we can expect that the rate was similar in pre-modern times.

http://birthnerd.blogspot.ca/2011/07/pre-modern-death-in-childbirth.html .

https://www.tudorsociety.com/childbirth-in-medieval-and-tudor-times-by-sarah-bryson/ .

Medieval Lives - Birth, Marriage, Death (Series) - HuDa >> .

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLCpYM0jg1d5M0XcIp4yj2kZF4Cws07HgL .

Medieval Life - Birth, Children, Marriage, Death - Tony - playlist

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLtakTnKQQMCzgnwhkhJrO5NE2mTuE8eN4

Women, Medieval to 19th C: She Wolves, Harlots, Whores, Heroines, Queens, Scandalous - archanth >> .

Medieval Life - Birth, Children, Marriage, Death - Tony - playlist

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLtakTnKQQMCzgnwhkhJrO5NE2mTuE8eN4

Women, Medieval to 19th C: She Wolves, Harlots, Whores, Heroines, Queens, Scandalous - archanth >> .

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6EXGbIsrT_V07Mvj-PZGtRt .

Medieval Apocalypse - The Black Death (BBC Documentary)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=no5nYmrJTtU

The Great Plague - Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPe6BgzHWY0

Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh6kDNVPk54

Medieval Apocalypse The Black Death BBC Documentary

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffaoF0xkUTo

A Day In the Life Living With the Plague > .

Helen Castor - Missals & Medieval Marriage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ecrajqIAwaE

Helen Castor - Church Courts

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPZAHEMUGhc

Medieval Lives Birth, Marriage, Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4mx8BBF44M&list=PLDJIWiwfNABlJMU0LDmB_m4JORMnJnS4L

Medieval Society

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yh_CZSLMxGo

Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh6kDNVPk54

Knights and Chivalry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_ypna0s2II

The Tactics and Strategy of the Hundred Years War - Dr Helen Castor - GreshamCollege

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqnROmQces0

The Middle Ages

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZr2JvFQqLWT6EEHwJudBnutXs6M-swmH

Life in Medieval Europe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIqdBAJ7gZo

Society: Children, Women, Birth, Marriage, Death, Dance ; Medieval to Modern - archanth

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6EXGbIsrT_V07Mvj-PZGtRt

Women, Medieval to 19th C: She Wolves, Harlots, Whores, Heroines, Queens, Scandalous - archanth

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6FbLdIk0yyO6G8MUiJSJzS7

Terry Jones' Medieval Lives

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLcMNaTUIX_mbUTs2IIqXSgmhJd-SfXWME

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLHZk29-IIwv2TE1plW1zqnHeudeRaTmpG

Early & Medieval Church History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G4P_ls7G5tc

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLRgREWf4NFWZEd86aVEpQ7B3YxXPhUEf-

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=helen+castor+medieval+lives

Medieval Life - Birth, Children, Marriage, Death - Tony - playlist

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLtakTnKQQMCzgnwhkhJrO5NE2mTuE8eN4

Medieval Apocalypse - The Black Death (BBC Documentary)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=no5nYmrJTtU

The Great Plague - Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPe6BgzHWY0

Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh6kDNVPk54

Medieval Apocalypse The Black Death BBC Documentary

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffaoF0xkUTo

Helen Castor - Missals & Medieval Marriage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ecrajqIAwaE

Helen Castor - Church Courts

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPZAHEMUGhc

Medieval Lives Birth, Marriage, Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4mx8BBF44M&list=PLDJIWiwfNABlJMU0LDmB_m4JORMnJnS4L

Medieval Society

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yh_CZSLMxGo

Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh6kDNVPk54

Knights and Chivalry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_ypna0s2II

The Tactics and Strategy of the Hundred Years War - Dr Helen Castor - GreshamCollege

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqnROmQces0

The Middle Ages

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZr2JvFQqLWT6EEHwJudBnutXs6M-swmH

Life in Medieval Europe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIqdBAJ7gZo

Society: Children, Women, Birth, Marriage, Death, Dance ; Medieval to Modern - archanth

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6EXGbIsrT_V07Mvj-PZGtRt

Women, Medieval to 19th C: She Wolves, Harlots, Whores, Heroines, Queens, Scandalous - archanth

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6FbLdIk0yyO6G8MUiJSJzS7

Terry Jones' Medieval Lives

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLcMNaTUIX_mbUTs2IIqXSgmhJd-SfXWME

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLHZk29-IIwv2TE1plW1zqnHeudeRaTmpG

Early & Medieval Church History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G4P_ls7G5tc

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLRgREWf4NFWZEd86aVEpQ7B3YxXPhUEf-

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=helen+castor+medieval+lives

Pandemics & the Economy | The Lasting Effects of the Black Death > .

How did Medieval People respond to the Black Death? - same > .

Black Death Explained in 8 Minutes - CaHi > .

How did Medieval People respond to the Black Death? - same > .

Black Death Explained in 8 Minutes - CaHi > .

History of the Black Death - 1 - fph > .

History of the Black Death - 2 - fph > .

History of the Black Death - 3 - fph > .

Pandemics & the Economy | The Lasting Effects of the Black Death > .History of the Black Death - 2 - fph > .

History of the Black Death - 3 - fph > .

Medieval Apocalypse - The Black Death (BBC Documentary)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=no5nYmrJTtU

The Great Plague - Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPe6BgzHWY0

Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh6kDNVPk54

Medieval Apocalypse The Black Death BBC Documentary

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffaoF0xkUTo

A Day In the Life Living With the Plague > .

Helen Castor - Missals & Medieval Marriage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ecrajqIAwaE

Helen Castor - Church Courts

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPZAHEMUGhc

Medieval Lives Birth, Marriage, Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4mx8BBF44M&list=PLDJIWiwfNABlJMU0LDmB_m4JORMnJnS4L

Medieval Society

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yh_CZSLMxGo

Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh6kDNVPk54

Knights and Chivalry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_ypna0s2II

The Tactics and Strategy of the Hundred Years War - Dr Helen Castor - GreshamCollege

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqnROmQces0

The Middle Ages

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZr2JvFQqLWT6EEHwJudBnutXs6M-swmH

Life in Medieval Europe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIqdBAJ7gZo

Society: Children, Women, Birth, Marriage, Death, Dance ; Medieval to Modern - archanth

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6EXGbIsrT_V07Mvj-PZGtRt

Women, Medieval to 19th C: She Wolves, Harlots, Whores, Heroines, Queens, Scandalous - archanth

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6FbLdIk0yyO6G8MUiJSJzS7

Terry Jones' Medieval Lives

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLcMNaTUIX_mbUTs2IIqXSgmhJd-SfXWME

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLHZk29-IIwv2TE1plW1zqnHeudeRaTmpG

Early & Medieval Church History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G4P_ls7G5tc

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLRgREWf4NFWZEd86aVEpQ7B3YxXPhUEf-

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=helen+castor+medieval+lives

Medieval Life - Birth, Children, Marriage, Death - Tony - playlist

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLtakTnKQQMCzgnwhkhJrO5NE2mTuE8eN4

Medieval Apocalypse - The Black Death (BBC Documentary)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=no5nYmrJTtU

The Great Plague - Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPe6BgzHWY0

Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh6kDNVPk54

Medieval Apocalypse The Black Death BBC Documentary

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffaoF0xkUTo

Helen Castor - Missals & Medieval Marriage

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ecrajqIAwaE

Helen Castor - Church Courts

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPZAHEMUGhc

Medieval Lives Birth, Marriage, Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4mx8BBF44M&list=PLDJIWiwfNABlJMU0LDmB_m4JORMnJnS4L

Medieval Society

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yh_CZSLMxGo

Black Death

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rh6kDNVPk54

Knights and Chivalry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_ypna0s2II

The Tactics and Strategy of the Hundred Years War - Dr Helen Castor - GreshamCollege

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqnROmQces0

The Middle Ages

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZr2JvFQqLWT6EEHwJudBnutXs6M-swmH

Life in Medieval Europe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIqdBAJ7gZo

Society: Children, Women, Birth, Marriage, Death, Dance ; Medieval to Modern - archanth

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6EXGbIsrT_V07Mvj-PZGtRt

Women, Medieval to 19th C: She Wolves, Harlots, Whores, Heroines, Queens, Scandalous - archanth

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6FbLdIk0yyO6G8MUiJSJzS7

Terry Jones' Medieval Lives

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLcMNaTUIX_mbUTs2IIqXSgmhJd-SfXWME

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLHZk29-IIwv2TE1plW1zqnHeudeRaTmpG

Early & Medieval Church History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G4P_ls7G5tc

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLRgREWf4NFWZEd86aVEpQ7B3YxXPhUEf-

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=helen+castor+medieval+lives

Mos Teutonicus

Mos Teutonicus (Latin: the Germanic custom) was a postmortem funerary custom used in Europe in the Middle Ages as a means of transporting, and solemnly disposing of, the bodies of high status individuals. The process involved the removal of the flesh from the body, so that the bones of the deceased could be transported hygienically from distant lands back home.

German aristocrats were particularly concerned that burial should not take place in the Holy Land, but rather on home soil. The Florentine chronicler Boncompagno was the first to connect the procedure specifically with German aristocrats, and coins the phrase mos Teutonicus, meaning ‘the Germanic custom.'

English and French aristocrats generally preferred embalming to mos Teutonicus, involving the burial of the entrails and heart in a separate location from the corpse. One of the advantages of mos Teutonicus was that it was relatively economical in comparison with embalming, and was more hygienic.

Corpse preservation was very popular in mediaeval society. The decaying body was seen as a representative of something sinful and evil. Embalming and mos Teutonicus, along with tomb effigies, were a way of giving the corpse an illusion of stasis and removed the uneasy image of putrification and decay.

Mediaeval society generally regarded entrails as ignoble and there was no great solemnity attached to their disposal, especially among German aristocrats.

Medieval Life - Birth, Children, Marriage, Death, Education, Sex

Medieval Life - Birth, Children, Marriage, Death, Education, Sex -- Tony Blake

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLtakTnKQQMCzgnwhkhJrO5NE2mTuE8eN4&disable_polymer=true

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-DUn4N5LCE

Mortality childbirth -- developing nations

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/sep/24/why-do-women-still-die-giving-birth

Renaissance Education:

https://www.thegreatcoursesdaily.com/education-in-the-renaissance/

Medieval Superstition - Sex Education > .

History of Sex: The Middle Ages (Documentary) > .

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLtakTnKQQMCzgnwhkhJrO5NE2mTuE8eN4&disable_polymer=true

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-DUn4N5LCE

Mortality childbirth -- developing nations

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/sep/24/why-do-women-still-die-giving-birth

Renaissance Education:

https://www.thegreatcoursesdaily.com/education-in-the-renaissance/

Medieval Superstition - Sex Education > .

History of Sex: The Middle Ages (Documentary) > .

Medieval Upheavals

1215 – Magna Carta

A charter agreed to by King John of England and his rebellious barons, the document would come to be seen as the beginning of legal limits on the power of monarchs.

A charter agreed to by King John of England and his rebellious barons, the document would come to be seen as the beginning of legal limits on the power of monarchs.

1315-17 – Great Famine

A series of crop failures and bad weather that struck large parts of Europe.

1337 – Beginning of the Hundred Years’ War

The Kings of England and France begin a war – fought off and on – that would last until 1453.

1347-51 – Black Death

One of the largest pandemics in human history, it crossed through Eurasia and killed as many as 200 million people.

1378 – Western Schism begins

A split within the Catholic churches that would see two or three men claiming to be Pope at the same time.

Labels:

14thC,

agriculture,

crisis,

documentation,

food,

legal,

plague,

religion,

warfare

Plagues & Pandemics

Plague in the Ancient and Medieval World - same > .

History of Pandemics mapped > .

Pandemics Economically Worse than War - First Pandemic - Pandemic Hx 1 - tgh > .

Life After the Black Death Ended - Weird > .

The Most Destructive Pandemics and Epidemics In Human History > .

Pandemics & the Economy | The Lasting Effects of the Black Death > .

How did Medieval People respond to the Black Death? - same > .

Black Death Explained in 8 Minutes - CaHi > .

The Most Destructive Pandemics and Epidemics In Human History > .

Pandemics & the Economy | The Lasting Effects of the Black Death > .

How did Medieval People respond to the Black Death? - same > .

Black Death Explained in 8 Minutes - CaHi > .

History of the Black Death - 1 - fph > .

History of the Black Death - 2 - fph > .

History of the Black Death - 3 - fph > .

Did The Black Death Affect Medieval Religion? Islam / Christianity ~ same > .

The Antonine Plague of 165 to 180 CE, also known as the Plague of Galen (from the name of the Greek physician living in the Roman Empire who described it), was an ancient pandemic brought to the Roman Empire by troops returning from campaigns in the Near East. Scholars have suspected it to have been either smallpox or measles, but the true cause remains undetermined.

History of the Black Death - 2 - fph > .

History of the Black Death - 3 - fph > .

Did The Black Death Affect Medieval Religion? Islam / Christianity ~ same > .

The Antonine Plague of 165 to 180 CE, also known as the Plague of Galen (from the name of the Greek physician living in the Roman Empire who described it), was an ancient pandemic brought to the Roman Empire by troops returning from campaigns in the Near East. Scholars have suspected it to have been either smallpox or measles, but the true cause remains undetermined.

Antonine Plague - 165 to 180 CE .

Justinian Plague: First Pandemic? // Procopius (541-542) - VoP > .

Pandemics Economically Worse than War - 1st Pandemic - Pandemic Hx 1 - tgh > .

The Plague of Justinian (541–542 CE, with recurrences until 750) was a pandemic that afflicted the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire and especially its capital, Constantinople, as well as the Sasanian Empire and port cities around the entire Mediterranean Sea.

In 2013, researchers confirmed earlier speculation that the cause of the Plague of Justinian was Yersinia pestis, the same bacterium responsible for the Black Death (1347–1351). ... Ancient and modern Yersinia pestis strains closely related to the ancestor of the Justinian plague strain have been found in Tian Shan, a system of mountain ranges on the borders of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and China, suggesting that the Justinian plague may have originated in or near that region.

The plague returned periodically until the eighth century. The waves of disease had a major effect on the subsequent course of European history.

Justinian Plague - 541 CE - - 750 CE .

Pandemics and the Shape of Human History: Outbreaks have sparked riots and propelled public-health innovations, prefigured revolutions and redrawn maps.

"In early 542, the plague struck Constantinople. The plague hit the powerless and the powerful alike. Justinian himself contracted it. Among the lucky, he survived. His rule, however, never really recovered. In the years leading up to 542, Justinian’s generals had reconquered much of the western part of the Roman Empire from the Goths, the Vandals, and other assorted barbarians. After 542, the Emperor struggled to recruit soldiers and to pay them. The territories that his generals had subdued began to revolt. The plague reached the city of Rome in 543, and seems to have made it all the way to Britain by 544. It broke out again in Constantinople in 558, a third time in 573, and yet again in 586.

Pandemics Economically Worse than War - 1st Pandemic - Pandemic Hx 1 - tgh > .

The Plague of Justinian (541–542 CE, with recurrences until 750) was a pandemic that afflicted the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire and especially its capital, Constantinople, as well as the Sasanian Empire and port cities around the entire Mediterranean Sea.

In 2013, researchers confirmed earlier speculation that the cause of the Plague of Justinian was Yersinia pestis, the same bacterium responsible for the Black Death (1347–1351). ... Ancient and modern Yersinia pestis strains closely related to the ancestor of the Justinian plague strain have been found in Tian Shan, a system of mountain ranges on the borders of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and China, suggesting that the Justinian plague may have originated in or near that region.

The plague returned periodically until the eighth century. The waves of disease had a major effect on the subsequent course of European history.

Justinian Plague - 541 CE - - 750 CE .

Pandemics and the Shape of Human History: Outbreaks have sparked riots and propelled public-health innovations, prefigured revolutions and redrawn maps.

"In early 542, the plague struck Constantinople. The plague hit the powerless and the powerful alike. Justinian himself contracted it. Among the lucky, he survived. His rule, however, never really recovered. In the years leading up to 542, Justinian’s generals had reconquered much of the western part of the Roman Empire from the Goths, the Vandals, and other assorted barbarians. After 542, the Emperor struggled to recruit soldiers and to pay them. The territories that his generals had subdued began to revolt. The plague reached the city of Rome in 543, and seems to have made it all the way to Britain by 544. It broke out again in Constantinople in 558, a third time in 573, and yet again in 586.

The Justinianic plague, as it became known, didn’t burn itself out until 750. By that point, there was a new world order. A powerful new religion, Islam, had arisen, and its followers ruled territory that included a great deal of what had been Justinian’s empire, along with the Arabian Peninsula. Much of Western Europe, meanwhile, had come under the control of the Franks. Rome had been reduced to about thirty thousand people, roughly the population of present-day Mamaroneck. Was the pestilence partly responsible? If so, history is written not only by men but also by microbes."

...

The word “quarantine” comes from the Italian quaranta, meaning “forty.” The earliest formal quarantines were a response to the Black Death, which, between 1347 and 1351, killed something like a third of Europe and ushered in what’s become known as the “second plague pandemic.” As with the first, the second pandemic worked its havoc fitfully. Plague would spread, then abate, only to flare up again.

During one such flareup, in the fifteenth century, the Venetians erected lazarettos—or isolation wards—on outlying islands, where they forced arriving ships to dock. The Venetians believed that by airing out the ships they were dissipating plague-causing vapors. If the theory was off base, the results were still salubrious; forty days gave the plague time enough to kill infected rats and sailors. Snowden, a professor emeritus at Yale, calls such measures one of the first forms of “institutionalized public health” and argues that they helped legitimatize the “accretion of power” by the modern state.

...

The word “quarantine” comes from the Italian quaranta, meaning “forty.” The earliest formal quarantines were a response to the Black Death, which, between 1347 and 1351, killed something like a third of Europe and ushered in what’s become known as the “second plague pandemic.” As with the first, the second pandemic worked its havoc fitfully. Plague would spread, then abate, only to flare up again.

During one such flareup, in the fifteenth century, the Venetians erected lazarettos—or isolation wards—on outlying islands, where they forced arriving ships to dock. The Venetians believed that by airing out the ships they were dissipating plague-causing vapors. If the theory was off base, the results were still salubrious; forty days gave the plague time enough to kill infected rats and sailors. Snowden, a professor emeritus at Yale, calls such measures one of the first forms of “institutionalized public health” and argues that they helped legitimatize the “accretion of power” by the modern state.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/04/06/pandemics-and-the-shape-of-human-history .

Plague writers who "predicted" coronavirus pandemic .

Pandemic and 1918: How History and Illness Intertwine - tHG > .

History of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic - tHG > .

Ж Black Death to Peasants' Revolt ..

Ж Black Death - Impacts ..Plague writers who "predicted" coronavirus pandemic .

Pandemic and 1918: How History and Illness Intertwine - tHG > .

History of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic - tHG > .

Ж Black Death to Peasants' Revolt ..

ЖЉ Black Death - Jewish Persecution, Europe ..

Cooling - Medieval famine, plague, social change ..

Crises ..

Economic & Societal Consequences of Black Death ..

Great Pestilence ..

History of Pandemics ..

Plague ..

Quarantine ..

Labels:

14thC,

1st millennium,

ancient,

Britain,

crisis,

economy,

Europe,

health,

history,

medieval,

plague,

society,

superstition

Sweating Sickness

Wharram Percy & Superstition

Experts said it was the first evidence of ancient [superstitious] practices to stop "corpses rising from their graves, spreading disease and assaulting the living".

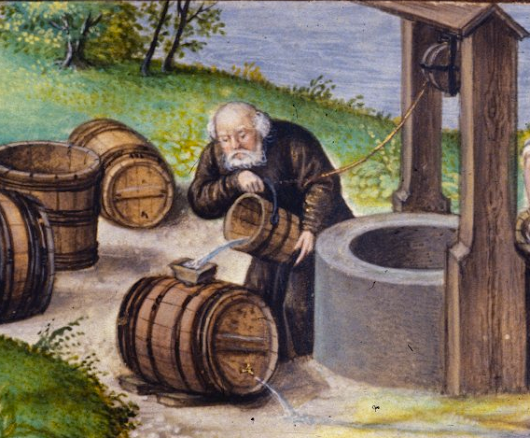

Water - risks of drinking

People in the Middle Ages were also well aware that not all water was safe to drink – in addition to polluted water, which would be largely confined to urban areas, it was common knowledge to avoid obtaining water from marshy areas or places of standing water. However, if they knew the water was coming from a good source, they would not be afraid to drink from it. Like us, they just did not boast about it.

𝕸 Economy

Daily Life ..

Economic History ..Economy of Roman Empire ➧

European Bank Money Creation - History ..

guild ..

Medieval Banking ..

Papyrus ..

₤ Prices ..

Tudor Xmas ..

Urban & Commercial Life in Medieval England and Europe ..

Usury, moneylending - Statute of the Jewry 1275, Edict of Expulsion 1290 ..

Usury, moneylending - Statute of the Jewry 1275, Edict of Expulsion 1290 ..

Educational Systems

Economic & Societal Consequences of Black Death

Pandemics & the Economy | The Lasting Effects of the Black Death - GC+ > .

How did Medieval People respond to the Black Death? - same > .

How did Medieval People respond to the Black Death? - same > .

History of Pandemics mapped > .

Black Death Explained in 8 Minutes - CaHi > .

Socio-economic & Political Impacts of the Black Death:

Black Death Explained in 8 Minutes - CaHi > .

History of the Black Death - 2 - fph > .

History of the Black Death - 3 - fph > .

Misconceptions about the Middle Ages - Dr Eleanor Janega & Jason Kingsley > .

History of the Black Death - 3 - fph > .

Misconceptions about the Middle Ages - Dr Eleanor Janega & Jason Kingsley > .

It is important to remember that past pandemics were far more deadly than coronavirus, which has a relatively low death rate.

Without modern medicine and institutions like the World Health Organization, past populations were more vulnerable. It is estimated that the Justinian plague of 541 AD killed 25 million and the Spanish flu of 1918 around 50 million.

By far the worst death rate in history was inflicted by the Black Death. Caused by several forms of plague, it lasted from 1348 to 1350, killing anywhere between 75 million and 200 million people worldwide and perhaps one half of the population of England. The economic consequences were also profound.

The majority of those who survived went on to enjoy improved standards of living. Prior to the Black Death, England had suffered from severe overpopulation.

Following the pandemic, the shortage of manpower led to a rise in the daily wages of labourers, as they were able to market themselves to the highest bidder. The diets of labourers also improved and included more meat, fresh fish, white bread and ale. Although landlords struggled to find tenants for their lands, changes in forms of tenure improved estate incomes and reduced their demands.

Following the pandemic, the shortage of manpower led to a rise in the daily wages of labourers, as they were able to market themselves to the highest bidder. The diets of labourers also improved and included more meat, fresh fish, white bread and ale. Although landlords struggled to find tenants for their lands, changes in forms of tenure improved estate incomes and reduced their demands.

But this attempt to regulate the market did not work. Enforcement of the labour legislation led to evasion and protests. In the longer term, real wages rose as the population level stagnated with recurrent outbreaks of the plague.

Landlords struggled to come to terms with the changes in the land market as a result of the loss in population. There was large-scale migration after the Black Death as people took advantage of opportunities to move to better land or pursue trade in the towns. Most landlords were forced to offer more attractive deals to ensure tenants farmed their lands.

A new middle class of men (almost always men) emerged. These were people who were not born into the landed gentry but were able to make enough surplus wealth to purchase plots of land. Recent research has shown that property ownership opened up to market speculation.

This revolt, the largest ever seen in England, came as a direct consequence of the recurring outbreaks of plague and government attempts to tighten control over the economy and pursue its international ambitions. The rebels claimed that they were too severely oppressed, that their lords “treated them as beasts”.

https://theconversation.com/what-can-the-black-death-tell-us-about-the-global-economic-consequences-of-a-pandemic-132793 .

"[In response to the drastic reduction of the labour force] influential employers, such as large landowners, lobbied the English crown to pass the Ordinance of Laborers, which informed workers that they were “obliged to accept the employment offered” for the same measly wages as before.

https://theconversation.com/what-can-the-black-death-tell-us-about-the-global-economic-consequences-of-a-pandemic-132793 .

"[In response to the drastic reduction of the labour force] influential employers, such as large landowners, lobbied the English crown to pass the Ordinance of Laborers, which informed workers that they were “obliged to accept the employment offered” for the same measly wages as before.

As successive waves of plague shrunk the work force, hired hands and tenants “took no notice of the king’s command,” as the Augustinian clergyman Henry Knighton complained. “If anyone wanted to hire them he had to submit to their demands, for either his fruit and standing corn would be lost or he had to pander to the "arrogance and greed" [this from the arrogant, greedy medieval Church] of the workers.”

As a result of this shift in the balance between labor and capital, we now know, thanks to painstaking research by economic historians, that real incomes of unskilled workers doubled across much of Europe within a few decades. According to tax records that have survived in the archives of many Italian towns, wealth inequality in most of these places plummeted. In England, workers ate and drank better than they did before the plague and even wore fancy furs that used to be reserved for their betters. At the same time, higher wages and lower rents squeezed landlords, many of whom failed to hold on to their inherited privilege. Before long, there were fewer lords and knights, endowed with smaller fortunes, than there had been when the plague first struck....

Looking at the historical record across Europe during the late Middle Ages, we see that elites did not readily cede ground, even under extreme pressure after a pandemic. During the Great Rising of England’s peasants in 1381, workers demanded, among other things, the right to freely negotiate labor contracts. Nobles and their armed levies put down the revolt by force, in an attempt to coerce people to defer to the old order. But the last vestiges of feudal obligations soon faded. Workers could hold out for better wages, and landlords and employers broke ranks with each other to compete for scarce labor.

As a result of this shift in the balance between labor and capital, we now know, thanks to painstaking research by economic historians, that real incomes of unskilled workers doubled across much of Europe within a few decades. According to tax records that have survived in the archives of many Italian towns, wealth inequality in most of these places plummeted. In England, workers ate and drank better than they did before the plague and even wore fancy furs that used to be reserved for their betters. At the same time, higher wages and lower rents squeezed landlords, many of whom failed to hold on to their inherited privilege. Before long, there were fewer lords and knights, endowed with smaller fortunes, than there had been when the plague first struck....

Looking at the historical record across Europe during the late Middle Ages, we see that elites did not readily cede ground, even under extreme pressure after a pandemic. During the Great Rising of England’s peasants in 1381, workers demanded, among other things, the right to freely negotiate labor contracts. Nobles and their armed levies put down the revolt by force, in an attempt to coerce people to defer to the old order. But the last vestiges of feudal obligations soon faded. Workers could hold out for better wages, and landlords and employers broke ranks with each other to compete for scarce labor.

Elsewhere, however, repression carried the day. In late medieval Eastern Europe, from Prussia and Poland to Russia, nobles colluded to impose serfdom on their peasantries to lock down a depleted labor force. This altered the long-term economic outcomes for the entire region: Free labor and thriving cities drove modernization in western Europe, but in the eastern periphery, development fell behind. [As is already happening in the USA.]

Farther south, the Mamluks of Egypt, a regime of foreign conquerors of Turkic origin, maintained a united front to keep their tight control over the land and continue exploiting the peasantry. The Mamluks forced the dwindling subject population to hand over the same rent payments, in cash and kind, as before the plague. This strategy sent the economy into a tailspin as farmers revolted or abandoned their fields.

But more often than not, repression failed. The first known plague pandemic in Europe and the Middle East, which started in 541, provides the earliest example. Anticipating the English Ordinance of Laborers by 800 years, the Byzantine emperor Justinian railed against scarce workers who “demand double and triple wages and salaries, in violation of ancient customs” and forbade them “to yield to the detestable passion of avarice” — to charge market wages for their labor. The doubling or tripling of real incomes reported on papyrus documents from the Byzantine province of Egypt leaves no doubt that his decree fell on deaf ears."https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/opinion/coronavirus-economy-history.html .

Plague in the Ancient and Medieval World - same > .

Ж Black Death - Impacts ..

Quarantine ..

Economic History

Feifs to Economic Liberalism - BeFa > .

A fief (L: feudum) was the central element of feudalism. It consisted of heritable property or rights granted by an overlord to a vassal who held it in fealty (or "in fee") in return for a form of feudal allegiance and service, usually given by the personal ceremonies of homage and fealty. The fees were often lands or revenue-producing real property held in feudal land tenure: these are typically known as fiefs or fiefdoms. However, not only land but anything of value could be held in fee, including governmental office, rights of exploitation such as hunting or fishing, monopolies in trade, and tax farms.

Forest Law & Forest of Dean

Magna Carta concession to forest access > .

Magna Carta accedes to dis-afforestation > .

What was the Charter of the Forest? | Magna Carta Series > .

Carta Foresta 1217 - TrId >> .

Ray Mears: Forest of Dean Wild Britain S01E01 Deciduous Forest

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bhnBhObR5QU

The Forest of Dean lies in west Gloucestershire in the angle formed by the rivers Severn and Wye as they approach their confluence. A large tract of woodland and waste land there was reserved for royal hunting before 1066 and survived into the modern period as one of the principal Crown forests in England, the largest after the New Forest. The name Forest of Dean was recorded from c. 1080 and was probably taken from the valley on the north-east of the area, where a manor called Dean was the Forest's administrative centre in the late 11th century.

In modern times the name Forest of Dean was sometimes used loosely for the part of Gloucestershire between the Severn and Wye, but all that land belonged to the Forest (used in the specific sense of the area subject to the forest law) only for a period in the early Middle Ages. In the 13th century the Forest's bounds were the two rivers and it extended northwards as far as Ross-on-Wye (Herefs.), Newent, and Gloucester; it then included 33 Gloucestershire and Herefordshire parishes, besides a central, uncultivated area which the Crown retained in demesne. Revised bounds, perambulated in 1300 and accepted by the Crown in 1327, reduced the extent of the Forest to the royal demesne and 14 parishes or parts of parishes, most of them, like the demesne itself, in St. Briavels hundred. The royal demesne remained extraparochial until the 1840s when, villages and hamlets having grown up within it, it was formed into the civil townships (later parishes) of East Dean and West Dean and into ecclesiastical districts.

......

The formerly extraparochial land of the Forest of Dean lies mainly at over 200 m. (656 ft.), reaching its highest point, 290 m. (951 ft.), at Ruardean hill in the north. Sometimes described as a plateau but actually comprising steep ridges and the valleys of streams draining to the Severn and Wye, its boundaries with the surrounding cultivated and ancient parochial lands are in most places defined by a scarp where the underlying carboniferous limestone of the region outcrops. On the west, however, the limestone outcrops at a shallower angle and there is a less obvious distinction in height between the Forest and the cultivated land of the large ancient parish of Newland. The long valley of Cannop brook, earlier called the Newerne stream, crosses the west part of the Forest from north to south, and a stream called in its northern part Cinderford brook and in its southern Soudley brook forms a long winding valley through the east part. Blackpool brook, so called by 1282, carves another deep valley through the south-eastern edge of the high land to meet Soudley brook at Blakeney below the Forest's scarp, and at the Forest's northern edge Greathough brook, formerly Lyd brook, descends a valley to the Wye. The streams were dammed in places for ironworks, notably in the Cannop valley where two large ponds were made in the 1820s to provide power for works at Parkend. Other large ponds on a tributary stream of Soudley brook at Sutton bottom, near Soudley, were built as fishponds in the mid 19th century for a privately-owned estate in that part of the Forest called Abbots wood. In the late 20th century the Forestry Commission maintained the Forest's ponds as nature reserves and as a public amenity; new ones were made at Woorgreen, near the centre of the Forest, as part of landscape restoration following opencast coal mining in the 1970s, and at Mallards Pike, near the head of Blackpool brook, in 1980.

Geology has given the Forest its rich industrial history. The land is formed of basin-shaped strata of the Carboniferous series. Underlying and outcropping at the rim are limestones which, especially the stratum called Crease Limestone, contain deposits of iron ore. Above are beds of sandstone, shale, and coal. The lowest bed of sandstone is known by the local name of Drybrook Sandstone, and the highest is the Pennant Sandstone. There are over 20 separate coal seams, varying in thickness from a few inches to 5 ft., the highest yielding being the Coleford High Delf which rises close to the surface near the rim of the Forest. Surface workings, shallow pits, or levels driven into the hillsides were the means of winning the iron ore and coal until the late 18th century when deeper mines were sunk. There were also numerous quarries, notably those in the Pennant Sandstone at Bixhead and elsewhere on the west side of the Cannop valley; that stone, which varies in colour but is mainly dark grey, was the principal building material used in the Forest's 19th-century industrial hamlets.

The Forest was most significant as a producer of oak timber, which was the principal reason for its survival in the modern period. Until the early 17th century, however, there was as much beech as oak among its large timber trees, and chestnut trees once grew in profusion on the north-east side of the Forest near Flaxley and gave the name by 1282 to a wood called the Chestnuts. The underwood was composed of a variety of small species such as hazel, birch, sallow, holly, and alder. The ancient forest contained many open areas. In 1282 various 'lands', or forest glades, maintained by the Crown presumably as grazing for the deer, included several with names later familiar in the Forest's history, Kensley, Moseley, Cannop, Crump meadow, and Whitemead (later a part of Newland parish). Numerous smaller clearings called 'trenches' had also been made as corridors alongside roads for securing travellers against ambush or for the grazing and passage of the deer. Larger areas of waste, or 'meends', such as Clearwell Meend and Mitcheldean Meend, lay on the borders adjoining the manorial lands, whose inhabitants used them for commoning their animals.

Although the royal demesne land was without permanent habitation until the early modern period, it was crossed by many ancient tracks, used by ironworkers, miners, and charcoal burners; large numbers, many termed 'mersty' (meaning a boundary path), were recorded in 1282 in a perambulation of the Forest bailiwicks, its administrative divisions. One of the more important ancient routes, known as the Dean road, had a pitched stone surface and borders of kerbstones. It ran between Lydney and Mitcheldean across the eastern part of the demesne by way of Oldcroft, a crossing of Blackpool brook, recorded as Blackpool ford in 1282, and a crossing of Soudley brook at Upper Soudley. The survival of much pitching and kerbing after the road went out of use in the turnpike era, and the possibility that it had linked two important Roman sites at Lydney and Ariconium, in Weston under Penyard (Herefs.), has led to the suggestion that it was a Roman road, though much of the stonework probably dates from the medieval and early modern periods; an estimate was made for renewing long stretches of the road, including the provision of new border stones, as late as the 1760s.

Two main routes crossed the extraparochial Forest from north-east to south-west and on them were sited the principal points of reference in a terrain with few landmarks. A route from the Severn crossing at Newnham to Monmouth recorded in 1255, when 'trenches' were ordered to be made beside it, was presumably that through Littledean, the central Forest, and Coleford. It entered over a high ridge west of Littledean, where a hermitage of St. White had been founded by 1225, and crossed Soudley (or Cinderford) brook at the place called Cinder ford in 1258, long before its name was taken by the principal settlement of the extraparochial Forest that formed on the hillside to the north-east of the crossing. Further west, near the centre of the Forest, the road passed the clearing called Kensley, where a courthouse stood by 1338 close to the site of the later Speech House, and crossed Newerne (or Cannop) brook at Cannop. The road emerged into the cultivated land of Coleford tithing at a place later called Broadwell Lane End, where a tree called Woolman oak in 1608 (fn. 34) was probably the 'W(o)lfmyen' oak which in 1282 was a landmark at the boundary of four of the Forest's bailiwicks. The other main route, recorded in 1282 as the high road to Monmouth, was that crossing the high north-western part of the extraparochial land from Mitcheldean, by way of Nailbridge, Brierley, Mirystock, where it crossed a tributary of Cannop brook above Lydbrook, to Coleford. The two remained the principal routes through the Forest but the northern one, described in the 1760s as the great road through the Forest from Gloucester to South Wales, was much altered in its course by later improvements.

The rivers Severn and Wye played a vital role in the development of Dean's industry but few of the various tracks and hollow ways that led from the central Forest to riverside landing-places and ferries were usable other than by packhorses before the 19th century. One of the few routes negotiable by wagons and timber rigs was the central main road out to Littledean with its branch down to Newnham; that was the usual route for carrying timber out of the Forest in 1737 when the Crown was asked to assist Newnham parish to repair part of it. Later in the 18th century a road leading from the south part of the woodlands by way of Parkend and Viney Hill to Gatcombe and Purton on the Severn became the principal route for timber destined for the naval dockyards.

The Crown's hunting rights, which provided the original motive for the Forest's preservation, were much used in the 13th century. The frequent orders made at the period for taking deer for gifts by the Crown and to meet the needs of the royal household suggest that fallow deer were the majority species in Dean, with red deer and roe present in smaller numbers. In 1278 the Forest was sufficiently well stocked for royal huntsmen to take 100 fallow bucks. At that period all three species of deer were classed as beasts of the forest, reserved for the exclusive use of the Crown, but roe were not classified as such after 1340.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol5/pp285-294

Forest of Dean: Forest administration

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol5/pp354-377

Forest of Dean: search

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/search?query=forest%20of%20dean

Magna Carta accedes to dis-afforestation > .

What was the Charter of the Forest? | Magna Carta Series > .

Carta Foresta 1217 - TrId >> .

Ray Mears: Forest of Dean Wild Britain S01E01 Deciduous Forest

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bhnBhObR5QU

The Forest of Dean lies in west Gloucestershire in the angle formed by the rivers Severn and Wye as they approach their confluence. A large tract of woodland and waste land there was reserved for royal hunting before 1066 and survived into the modern period as one of the principal Crown forests in England, the largest after the New Forest. The name Forest of Dean was recorded from c. 1080 and was probably taken from the valley on the north-east of the area, where a manor called Dean was the Forest's administrative centre in the late 11th century.

In modern times the name Forest of Dean was sometimes used loosely for the part of Gloucestershire between the Severn and Wye, but all that land belonged to the Forest (used in the specific sense of the area subject to the forest law) only for a period in the early Middle Ages. In the 13th century the Forest's bounds were the two rivers and it extended northwards as far as Ross-on-Wye (Herefs.), Newent, and Gloucester; it then included 33 Gloucestershire and Herefordshire parishes, besides a central, uncultivated area which the Crown retained in demesne. Revised bounds, perambulated in 1300 and accepted by the Crown in 1327, reduced the extent of the Forest to the royal demesne and 14 parishes or parts of parishes, most of them, like the demesne itself, in St. Briavels hundred. The royal demesne remained extraparochial until the 1840s when, villages and hamlets having grown up within it, it was formed into the civil townships (later parishes) of East Dean and West Dean and into ecclesiastical districts.

......

The formerly extraparochial land of the Forest of Dean lies mainly at over 200 m. (656 ft.), reaching its highest point, 290 m. (951 ft.), at Ruardean hill in the north. Sometimes described as a plateau but actually comprising steep ridges and the valleys of streams draining to the Severn and Wye, its boundaries with the surrounding cultivated and ancient parochial lands are in most places defined by a scarp where the underlying carboniferous limestone of the region outcrops. On the west, however, the limestone outcrops at a shallower angle and there is a less obvious distinction in height between the Forest and the cultivated land of the large ancient parish of Newland. The long valley of Cannop brook, earlier called the Newerne stream, crosses the west part of the Forest from north to south, and a stream called in its northern part Cinderford brook and in its southern Soudley brook forms a long winding valley through the east part. Blackpool brook, so called by 1282, carves another deep valley through the south-eastern edge of the high land to meet Soudley brook at Blakeney below the Forest's scarp, and at the Forest's northern edge Greathough brook, formerly Lyd brook, descends a valley to the Wye. The streams were dammed in places for ironworks, notably in the Cannop valley where two large ponds were made in the 1820s to provide power for works at Parkend. Other large ponds on a tributary stream of Soudley brook at Sutton bottom, near Soudley, were built as fishponds in the mid 19th century for a privately-owned estate in that part of the Forest called Abbots wood. In the late 20th century the Forestry Commission maintained the Forest's ponds as nature reserves and as a public amenity; new ones were made at Woorgreen, near the centre of the Forest, as part of landscape restoration following opencast coal mining in the 1970s, and at Mallards Pike, near the head of Blackpool brook, in 1980.

Geology has given the Forest its rich industrial history. The land is formed of basin-shaped strata of the Carboniferous series. Underlying and outcropping at the rim are limestones which, especially the stratum called Crease Limestone, contain deposits of iron ore. Above are beds of sandstone, shale, and coal. The lowest bed of sandstone is known by the local name of Drybrook Sandstone, and the highest is the Pennant Sandstone. There are over 20 separate coal seams, varying in thickness from a few inches to 5 ft., the highest yielding being the Coleford High Delf which rises close to the surface near the rim of the Forest. Surface workings, shallow pits, or levels driven into the hillsides were the means of winning the iron ore and coal until the late 18th century when deeper mines were sunk. There were also numerous quarries, notably those in the Pennant Sandstone at Bixhead and elsewhere on the west side of the Cannop valley; that stone, which varies in colour but is mainly dark grey, was the principal building material used in the Forest's 19th-century industrial hamlets.

The Forest was most significant as a producer of oak timber, which was the principal reason for its survival in the modern period. Until the early 17th century, however, there was as much beech as oak among its large timber trees, and chestnut trees once grew in profusion on the north-east side of the Forest near Flaxley and gave the name by 1282 to a wood called the Chestnuts. The underwood was composed of a variety of small species such as hazel, birch, sallow, holly, and alder. The ancient forest contained many open areas. In 1282 various 'lands', or forest glades, maintained by the Crown presumably as grazing for the deer, included several with names later familiar in the Forest's history, Kensley, Moseley, Cannop, Crump meadow, and Whitemead (later a part of Newland parish). Numerous smaller clearings called 'trenches' had also been made as corridors alongside roads for securing travellers against ambush or for the grazing and passage of the deer. Larger areas of waste, or 'meends', such as Clearwell Meend and Mitcheldean Meend, lay on the borders adjoining the manorial lands, whose inhabitants used them for commoning their animals.

Although the royal demesne land was without permanent habitation until the early modern period, it was crossed by many ancient tracks, used by ironworkers, miners, and charcoal burners; large numbers, many termed 'mersty' (meaning a boundary path), were recorded in 1282 in a perambulation of the Forest bailiwicks, its administrative divisions. One of the more important ancient routes, known as the Dean road, had a pitched stone surface and borders of kerbstones. It ran between Lydney and Mitcheldean across the eastern part of the demesne by way of Oldcroft, a crossing of Blackpool brook, recorded as Blackpool ford in 1282, and a crossing of Soudley brook at Upper Soudley. The survival of much pitching and kerbing after the road went out of use in the turnpike era, and the possibility that it had linked two important Roman sites at Lydney and Ariconium, in Weston under Penyard (Herefs.), has led to the suggestion that it was a Roman road, though much of the stonework probably dates from the medieval and early modern periods; an estimate was made for renewing long stretches of the road, including the provision of new border stones, as late as the 1760s.

Two main routes crossed the extraparochial Forest from north-east to south-west and on them were sited the principal points of reference in a terrain with few landmarks. A route from the Severn crossing at Newnham to Monmouth recorded in 1255, when 'trenches' were ordered to be made beside it, was presumably that through Littledean, the central Forest, and Coleford. It entered over a high ridge west of Littledean, where a hermitage of St. White had been founded by 1225, and crossed Soudley (or Cinderford) brook at the place called Cinder ford in 1258, long before its name was taken by the principal settlement of the extraparochial Forest that formed on the hillside to the north-east of the crossing. Further west, near the centre of the Forest, the road passed the clearing called Kensley, where a courthouse stood by 1338 close to the site of the later Speech House, and crossed Newerne (or Cannop) brook at Cannop. The road emerged into the cultivated land of Coleford tithing at a place later called Broadwell Lane End, where a tree called Woolman oak in 1608 (fn. 34) was probably the 'W(o)lfmyen' oak which in 1282 was a landmark at the boundary of four of the Forest's bailiwicks. The other main route, recorded in 1282 as the high road to Monmouth, was that crossing the high north-western part of the extraparochial land from Mitcheldean, by way of Nailbridge, Brierley, Mirystock, where it crossed a tributary of Cannop brook above Lydbrook, to Coleford. The two remained the principal routes through the Forest but the northern one, described in the 1760s as the great road through the Forest from Gloucester to South Wales, was much altered in its course by later improvements.

The rivers Severn and Wye played a vital role in the development of Dean's industry but few of the various tracks and hollow ways that led from the central Forest to riverside landing-places and ferries were usable other than by packhorses before the 19th century. One of the few routes negotiable by wagons and timber rigs was the central main road out to Littledean with its branch down to Newnham; that was the usual route for carrying timber out of the Forest in 1737 when the Crown was asked to assist Newnham parish to repair part of it. Later in the 18th century a road leading from the south part of the woodlands by way of Parkend and Viney Hill to Gatcombe and Purton on the Severn became the principal route for timber destined for the naval dockyards.

The Crown's hunting rights, which provided the original motive for the Forest's preservation, were much used in the 13th century. The frequent orders made at the period for taking deer for gifts by the Crown and to meet the needs of the royal household suggest that fallow deer were the majority species in Dean, with red deer and roe present in smaller numbers. In 1278 the Forest was sufficiently well stocked for royal huntsmen to take 100 fallow bucks. At that period all three species of deer were classed as beasts of the forest, reserved for the exclusive use of the Crown, but roe were not classified as such after 1340.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol5/pp285-294

Forest of Dean: Forest administration

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol5/pp354-377

Forest of Dean: search

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/search?query=forest%20of%20dean

Fugger - Habsburg Banker

.Jakob Fugger - Banker Who Financed the Habsburgs - K&G > .

Jakob Fugger, German banker and businessman became one of the richest people of the late medieval period by introducing a number of new business practices and tying his fortune to the rising Habsburgs, financing them in becoming the hegemon power in Europe. His loans were crucial for the Habsburg victory at the battle of Pavia in 1525 (https://youtu.be/mcprW-tXuaA) and the election of Maximilian I.

Jakob Fugger of the Lily (Jakob Fugger von der Lilie; 6 March 1459 – 30 December 1525), also known as Jakob Fugger the Rich or sometimes Jakob II, was a major German merchant, mining entrepreneur, and banker. He was a descendant of the Fugger merchant family located in the Mixed Imperial City of Augsburg, where he was born and later also elevated through marriage to Grand Burgher of Augsburg (Großbürger zu Augsburg). Within a few decades he expanded the family firm to a business operating in all of Europe. He began his education at the age of 14 in Venice, which also remained his main residence until 1487. At the same time he was a cleric and held several prebendaries, even though he never lived in a monastery. With an inflation adjusted net worth of over $400 billion, Fugger is held to be one of the wealthiest individuals in modern history, alongside the early 20th century industrialists John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie. At the time of his death in 1525, Fugger's personal wealth was equivalent to 2% of the GDP of Europe.

The foundation of the family's wealth was created mainly by the textile trade with Italy. The company grew rapidly after the brothers Ulrich, Georg and Jakob began banking transactions with the House of Habsburg as well as the Roman Curia, and at the same time began mining operations in Tyrol, and from 1493 on the extraction of silver and copper in the kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary. As of 1525 they also had the right to mine quicksilver and cinnabar in Almadén.

After 1487, Jakob Fugger was the de facto head of the Fugger business operations which soon had an almost monopolistic hold on the European copper market. Copper from Hungary was transported through Antwerp to Lisbon, and from there shipped to India. Jakob Fugger also contributed to the first and only trade expedition to India that German merchants cooperated in, a Portuguese fleet to the Indian west coast (1505/06) as well as a failed Spanish trade expedition to the Maluku Islands.

With his support of the Habsburg dynasty as a banker he had a decisive influence on European politics at the time. He financed the rise of Maximilian I and made considerable contributions to secure the election of the Spanish king Charles I to become Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Jakob Fugger also funded the marriages which later resulted in the House of Habsburg gaining the kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary.

Jakob Fugger secured his legacy and lasting fame through his foundations in Augsburg. A chapel funded by him and built from 1509 to 1512 is Germany's first renaissance building and contains the tombs of the brothers Ulrich, Georg and Jakob. The Fuggerei which was founded by Jakob in 1521 is the world's oldest social housing complex still in use. The Damenhof, part of the Fuggerhäuser in Augsburg, is the first secular renaissance building in Germany and was built in 1515.

At his death on 30 December 1525, Jakob Fugger bequeathed to his nephew Anton Fugger company assets totaling 2,032,652 guilders. He is among the most well known Germans and arguably the most famous citizen of Augsburg, with his wealth earning him the moniker "Fugger the Rich". In 1967 a bust of him was placed in the Walhalla, a "hall of fame" near Regensburg that honors laudable and distinguished Germans.

The foundation of the family's wealth was created mainly by the textile trade with Italy. The company grew rapidly after the brothers Ulrich, Georg and Jakob began banking transactions with the House of Habsburg as well as the Roman Curia, and at the same time began mining operations in Tyrol, and from 1493 on the extraction of silver and copper in the kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary. As of 1525 they also had the right to mine quicksilver and cinnabar in Almadén.

After 1487, Jakob Fugger was the de facto head of the Fugger business operations which soon had an almost monopolistic hold on the European copper market. Copper from Hungary was transported through Antwerp to Lisbon, and from there shipped to India. Jakob Fugger also contributed to the first and only trade expedition to India that German merchants cooperated in, a Portuguese fleet to the Indian west coast (1505/06) as well as a failed Spanish trade expedition to the Maluku Islands.

With his support of the Habsburg dynasty as a banker he had a decisive influence on European politics at the time. He financed the rise of Maximilian I and made considerable contributions to secure the election of the Spanish king Charles I to become Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Jakob Fugger also funded the marriages which later resulted in the House of Habsburg gaining the kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary.

Jakob Fugger secured his legacy and lasting fame through his foundations in Augsburg. A chapel funded by him and built from 1509 to 1512 is Germany's first renaissance building and contains the tombs of the brothers Ulrich, Georg and Jakob. The Fuggerei which was founded by Jakob in 1521 is the world's oldest social housing complex still in use. The Damenhof, part of the Fuggerhäuser in Augsburg, is the first secular renaissance building in Germany and was built in 1515.

At his death on 30 December 1525, Jakob Fugger bequeathed to his nephew Anton Fugger company assets totaling 2,032,652 guilders. He is among the most well known Germans and arguably the most famous citizen of Augsburg, with his wealth earning him the moniker "Fugger the Rich". In 1967 a bust of him was placed in the Walhalla, a "hall of fame" near Regensburg that honors laudable and distinguished Germans.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)