800 years of rape culture: Rape in the Middle Ages was seen as a routine part of women’s lives, even as it was condemned.

Media portrayals of the Middle Ages often depict rape as a routine, legally sanctioned part of life for women, especially servants and peasants. They sensationalise medieval life and imply that things are so much better now by comparison, enabling us to bask in an unearned sense of progress. This fits with other popular ideas about that time period – that life back then was short and violent, marked by gaping disparities between nobles and commoners, and that women had no power whatsoever.

...

In England and Scotland between 1200 and 1600, rape – defined legally as a man having sex with a woman against her will and ‘by force’ – was considered a criminal offence, and there were laws in place to deal with rapists. Women themselves could press rape charges without the help of a father, brother or husband, in contrast to stereotypes of medieval women as helpless damsels in distress, dependent on men to come to their aid. Women could bear witness in court regarding their violation and try to seek justice and reparation. We can still hear their voices today in the form of survivor testimonies from medieval court records. These testimonies are often short on detail and laced with legal jargon, but we can nonetheless read them in the vein of present-day survivor narratives. While short and broad, the medieval documents nonetheless conjure ... traumas.

...

One case from Glasgow shows how survivor testimonies from the distant past can challenge our contemporary assumptions about medieval women, rape and power. A servant named Isobel Burne claimed that one John Anderson had tried to rape her by accosting her while she was at work. He threw her down on her back and hit her on the head with a clod of earth before ‘speaking sundry abominable words, not worthy of rehearsal’. Anderson confessed that Burne was telling the truth about her experience. As punishment, he was banished from the town ‘for the great offence to God and the slander to Isobel’. Even though Burne was a servant and a woman, the court sided with her rather than her more powerful assailant.

In another case, William de Hadestock and his wife Joan claimed in civil court that James de Montibus had broken into their home in London on a summer evening in 1269 with a group of armed men. One witness corroborated her account and testified that ‘after [James] had entered the house, he closed the door and tore [Joan’s] dress down to the navel, threw her to the ground and raped her, breaking her finger’. The court imprisoned Montibus until he could pay a hefty settlement of £5 to the couple. The rape, which actually occurred before Joan’s marriage to William, didn’t destroy her marital prospects. Instead, her new husband stood by her side in court as she sought justice and fought successfully for monetary compensation.

Other cases feature surprising or unexpected moments that show women seeking justice in a variety of ways. One case from Peebles in southern Scotland points to something resembling contemporary notions of restorative justice: in 1561, Robert Bullo was sentenced to appear before his local church congregation on a Sunday to ask publicly for Marion Stenson’s forgiveness after he raped her.

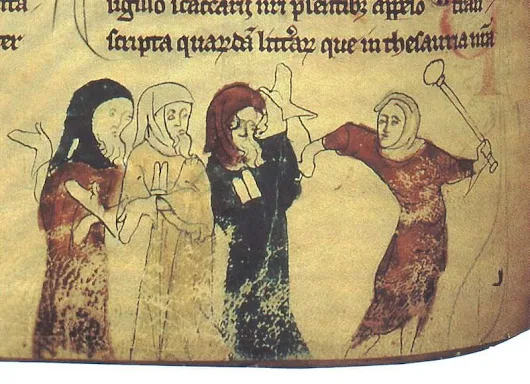

Some women took justice into their own hands. In a rural area of Shropshire near the Welsh border in 1405, Isabella Gronowessone and her two daughters ambushed Roger de Pulesdon in a field, tied a cord around his neck, cut off his testicles and stole his horse. All three women were subsequently pardoned, implying that they had exacted a brutal form of vigilante justice for rape.

Isabella Plomet won a substantial settlement in civil court in 1292 after her doctor drugged her with a narcotic surgical drink and raped her, demonstrating that intoxication-facilitated sexual assault was viewed as a violation that deserved restitution.

In medieval times, rape was categorised legally as a property crime, and thus a felony, with penalties such as castration, blinding or hanging. As you can imagine, criminal convictions for rape were very rare, since all-male juries were reluctant to condemn their fellow men to such harsh penalties on the basis of a woman’s claim, and these penalties were rarely enforced even when the assailant was convicted. Survivors had to follow several difficult steps in order to have any hope of conviction: they were required to report their rapes immediately and publicly, to recount identical narratives of their trauma multiple times to local court officials in their own jurisdiction as well as in neighbouring jurisdictions, and to show evidence of a violent attack – such as torn clothing, bloodstains, dishevelled hair or physical wounds – to ‘men of good repute’. If a survivor wanted to avoid this process or felt that another form of justice would be more fitting, she could negotiate for out-of-court restitution or file a civil case for monetary damages rather than pursuing criminal charges, as Joan de Hadestock chose to do after Montibus raped her in her home. This enabled women to receive tangible recompense for what they’d suffered, and to bypass a complicated and traumatic criminal justice process.

Numerous case records illustrate the inherent flaws and loopholes in medieval systems of rape justice, showing how women could find their charges dismissed if they’d had consensual sex with their rapist before the rape, or failed to follow complicated reporting procedures, or became pregnant from the attack. One case from Wiltshire illustrates the still-common myth that someone cannot claim rape if they previously consented to sex with their assailant: an unmarried woman named Edith claimed that William le Escot raped her in 1249. The record states: ‘It is testified that William lay with Edith but he did not violate her because she was already known to him.’ In other words, because Edith and Escot had had consensual sex in the past, this particular incident didn’t count as a violation. The case features intriguing additional details: Edith also accused a woman named Alice of helping to facilitate Escot’s rape and of stealing a brooch from her.

The pervasive distrust of women in medieval culture – illustrated by popular proverbs such as ‘women can lie and weep whenever they wish’ – meant that women faced an uphill battle in convincing juries that they’d been violated. Legal records repeatedly feature women who bring charges of rape and are subsequently charged with false reporting after the jury concludes that the accused is not guilty or that the victim didn’t properly report her assault.

In Wiltshire in 1249, an unmarried woman named Eve accused Adam Mikel of raping her. Mikel first refused to appear in court, then later denied her claim. The jury agreed that he wasn’t guilty, so Eve was arrested for bringing false charges. She was later pardoned because she was poor.

Other times, women were charged and imprisoned after failing to follow prohibitively specific and difficult reporting procedures. In 1248, Margery, daughter of Emma de la Hulle, testified that a man named Nicholas had raped her outdoors on a summer evening four years earlier, and that she had been a virgin at the time. She specified the location of the rape as ‘between Bagnor and Boxford in a certain place which is known as Kingestrete near Bagnor wood’; search for this certain place online today, and you’ll find maps for scenic walks through Bagnor Wood in West Berkshire. Margery supported her claim against Nicholas with confidence and courage, as the record states that ‘she offers to prove this against him as the court sees fit’. Nicholas responded that Margery didn’t report the assault in a timely fashion, and also neglected to bring her appeal to the neighbouring county court. The jury concluded that Margery’s failure to follow these procedures invalidated her rape charge, and they sentenced her to prison for false reporting, even as they also acknowledged that Nicholas had had sex with her, and required him to pay a fine.

One disturbing case backfired spectacularly against its victim, Joan Seler, an 11-year-old from London. Seler testified in 1321 that Reymund de Limoges had seized her by the left hand as she stood in the bustling street just a couple of feet from her father’s house at twilight. Limoges dragged her to his rented upstairs chamber and raped her there. The testimony is graphically detailed and agonising to read, in spite of its heavy use of legal jargon; Seler claimed that Limoges took her

between his two arms and against her consent and will laid her on the ground with her belly upwards and her back on the ground, and with his right hand raised the clothes of the same Joan the daughter of Eustace up to her navel, she being clothed in a blue coat and a shift of light cloth, and feloniously … with both his hands separated the legs and thighs of this same Joan, and with his right hand took his male organ of such and such a length and size and put it in the secret parts of this same Joan …

Seler added that the attack left her bleeding, and that Limoges kept her in his chamber all night before freeing her.

Limoges countered that Seler failed to first notify the local coroner of the rape, waited six months to bring charges against him rather than doing so within 40 days, and gave two different dates for the assault in two separate depositions: in one account, she’s claimed it had happened on a Sunday evening, and in another that it was on a Wednesday. Limoges asked the court to dismiss the case due to this discrepancy ‘because she could not twice be deprived of one and the same maidenhead’, joking about the very serious charges against him. The jury acquitted Limoges and ruled that he had sustained £40 in damages, which Seler – as an 11-year-old and a saddlemaker’s daughter – was of course unable to pay. The court ordered Seler be arrested, then pardoned because of her age.

Erroneous beliefs about consent and pregnancy enabled victims to be blamed and perpetrators to escape unpunished. Another verdict resting on such beliefs is the case of a 30-year-old woman named Joan who accused a man known as E of rape in 1313. She had an infant, whom she claimed was conceived from the attack. The jury concluded that this was a ‘miracle’ because ‘a child could not be engendered without the consent of both parties’. The jury exonerated E and sent Joan to prison for making a false report. The jury’s opinion echoed a popular 13th-century law book, which asserted that ‘no woman can conceive if she does not consent’.

...

Even though the medieval legal system designated rape as a crime and contained prosecution mechanisms such as castration, blinding or hanging, medieval culture – which influenced the authorities who wrote the laws as well as the juries who enforced them – enabled the loopholes that prevented many survivors from receiving the justice that they sought.

Medieval rape culture was based on several pervasive beliefs about women and sex – that women lie about rape; that they are naturally hornier than men and unable to control their desires; that they habitually change their minds about sex; and that rape must be proved with physical injuries, immediate outcry, repeated identical accounts of the trauma delivered to the proper authorities and copious tears in order to count as ‘real rape’. ...................