Љ Hereford .. Hill Forts .. Houndtor Deserted Medieval Village .. Hundred of Westbury .. Hundred, St Briavels .. Lindisfarne Priory .. Llanthony Secunda Priory .. London .. London & Suburbs 1872 .. London Prisons .. Lyndhurst .. Mappa Mundi .. Mapping .. Maps .. Mendip Hills .. Medieval London - Life and Death .. Medieval Maps .. Millbank 19th century prison .. New Forest WW2 .. Norrœna: Norðvegr .. Nova Foresta .. œ Old English Place Names .. Oppidum Gaulois, Lutèce, Paris .. Oxford .. Oxford, Woodstock .. Oxford City .. Pilgrims' Way .. Rhosan .. River Avon .. RiS - River Severn, Worcester, Malvern Hills .. River Severn .. River Thames .. River Wye .. Rivers of England, Major .. Rivers of Midlands .. Roman Roads of Britain .. Salisbury Cathedral Clock .. Satellite Imagery .. Severn Bore .. Severn Estuary .. Soton .. Southend .. Southampton .. St Briavels Hundred .. Stourbridge, Worcester .. Tamar Valley, Cornwall .. Tewkesbury .. Thames & Way Navigation .. Underground .. Wales .. Harlech Castle, Wales .. Warwickshire .. Weald .. Weald Ironworkers .. Westbury Hundred .. Westminster Palace - History .. Woodstock .. Worcester .. Worcester, Stourbridge .. Y Fenni .. Agisters, Verderers, Medieval Forest of Dean .. Forest of Dean, Clearwell Caves .. Gothic Architecture .. Medieval Construction .. Medieval Kitchens .. Medieval Window Coverings .. Truss Types ..

◊◊ Locations - Medieval, Modern

Abermynwy .. Abingdon .. Banstead .. Bath .. Beachley Peninsula .. Berkeley .. Birmingham 1300 .. Brighton .. Bristol .. British Camp Hill Fort .. Bunkers .. Caerllion & Caerwent - Isca Augusta & Venta Silurum .. Cas-gwent .. Caterham .. Chaldon .. Cheddar Gorge .. Chelsea Physic Garden .. Cheshire .. Chester .. Clearwell Caves, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire .. Cosmeston Medieval Village .. Cotswolds .. Dartmoor - Ancient Road of The Dead .. Dunwich - Disappearing Medieval Port .. Durham .. Forests .. Forest of Dean .. Forest of Dean Ironworking .. Ring Cairn, Forest of Dean, Bronze Age . .. Gloucester & Whitefriars .. Gloucestershire .. Gloucestershire, Clearwell Caves, Forest of Dean .. Gough Map .. Harlech Castle, Wales .. Hereford .. Hereford, 1290 Expulsion .. Kenilworth .. Kingsholm Palace .. Hailes Abbey, Cotswolds .. Hampshire .. Herefordshire ..

Љ Hereford .. Hill Forts .. Houndtor Deserted Medieval Village .. Hundred of Westbury .. Hundred, St Briavels .. Lindisfarne Priory .. Llanthony Secunda Priory .. London .. London & Suburbs 1872 .. London Prisons .. Lyndhurst .. Mappa Mundi .. Mapping .. Maps .. Mendip Hills .. Medieval London - Life and Death .. Medieval Maps .. Millbank 19th century prison .. New Forest WW2 .. Norrœna: Norðvegr .. Nova Foresta .. œ Old English Place Names .. Oppidum Gaulois, Lutèce, Paris .. Oxford .. Oxford, Woodstock .. Oxford City .. Pilgrims' Way .. Rhosan .. River Avon .. RiS - River Severn, Worcester, Malvern Hills .. River Severn .. River Thames .. River Wye .. Rivers of England, Major .. Rivers of Midlands .. Roman Roads of Britain .. Salisbury Cathedral Clock .. Satellite Imagery .. Severn Bore .. Severn Estuary .. Soton .. Southend .. Southampton .. St Briavels Hundred .. Stourbridge, Worcester .. Tamar Valley, Cornwall .. Tewkesbury .. Thames & Way Navigation .. Underground .. Wales .. Harlech Castle, Wales .. Warwickshire .. Weald .. Weald Ironworkers .. Westbury Hundred .. Westminster Palace - History .. Woodstock .. Worcester .. Worcester, Stourbridge .. Y Fenni .. Agisters, Verderers, Medieval Forest of Dean .. Forest of Dean, Clearwell Caves .. Gothic Architecture .. Medieval Construction .. Medieval Kitchens .. Medieval Window Coverings .. Truss Types ..

Љ Hereford .. Hill Forts .. Houndtor Deserted Medieval Village .. Hundred of Westbury .. Hundred, St Briavels .. Lindisfarne Priory .. Llanthony Secunda Priory .. London .. London & Suburbs 1872 .. London Prisons .. Lyndhurst .. Mappa Mundi .. Mapping .. Maps .. Mendip Hills .. Medieval London - Life and Death .. Medieval Maps .. Millbank 19th century prison .. New Forest WW2 .. Norrœna: Norðvegr .. Nova Foresta .. œ Old English Place Names .. Oppidum Gaulois, Lutèce, Paris .. Oxford .. Oxford, Woodstock .. Oxford City .. Pilgrims' Way .. Rhosan .. River Avon .. RiS - River Severn, Worcester, Malvern Hills .. River Severn .. River Thames .. River Wye .. Rivers of England, Major .. Rivers of Midlands .. Roman Roads of Britain .. Salisbury Cathedral Clock .. Satellite Imagery .. Severn Bore .. Severn Estuary .. Soton .. Southend .. Southampton .. St Briavels Hundred .. Stourbridge, Worcester .. Tamar Valley, Cornwall .. Tewkesbury .. Thames & Way Navigation .. Underground .. Wales .. Harlech Castle, Wales .. Warwickshire .. Weald .. Weald Ironworkers .. Westbury Hundred .. Westminster Palace - History .. Woodstock .. Worcester .. Worcester, Stourbridge .. Y Fenni .. Agisters, Verderers, Medieval Forest of Dean .. Forest of Dean, Clearwell Caves .. Gothic Architecture .. Medieval Construction .. Medieval Kitchens .. Medieval Window Coverings .. Truss Types ..

Location Posts

- Abingdon ..

- Berkeley ..

Birmingham 1300 ..

Bristol ..

- Chalk Downs & High Weald .. Weald Ironworkers ..

Chester, Cheshire ..

Commerce - markets, shops ..

- Deer Park ..

- Dunwich - Disappearing Medieval Port ..

Durham ..

England at the beginning of the civil war, 1643 ..

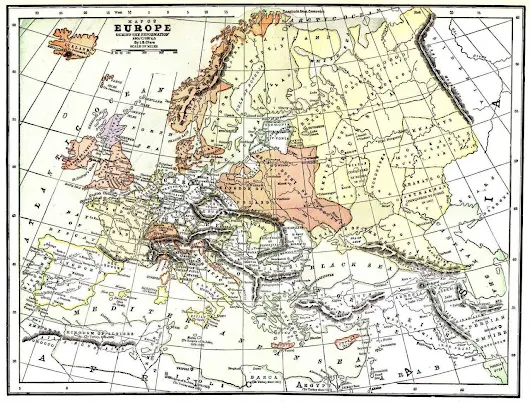

Europe - map, 1550 ..

Forests: Forest of Dean .. Forest of Dean - ironworking .. Forest Law & Forest of Dean .. (Legal History) .. Forest of Dean - Puzzlewood .. Forest of Dean, Ring Cairn, Bronze Age . .. Hundred of Westbury .. St. Briavels hundred ..

Gloucester - medieval .. Gloucestershire .. Gloucester topography .. Gloucestershire .. Gloucester Castle .. Kingholm Palace ..

Verderers: Agisters, Verderers, Medieval Forest of Dean, New Forest ..

New Forest: Nova Foresta .

Herefordshire ..

Herefordshire ..

Hill Forts ..

Lindisfarne Priory ..

London Prisons ..

London Prisons ..

- Mappa Mundi ..

- Mapping ..

- Medieval Maps ..

Millbank 19th century prison ..

Oppidum Gaulois, Lutèce, Paris ..

Oxford .. Oxford, Woodstock ..

Paris & Notre Dame ..

Rivers - Major Rivers of England ..

Thames - River Thames ..

London - Tudor

Medieval towns, villages

New Forest

Tamar Valley, Cornwall ..

Town & Country: Agisters, Archaeology, Forests, History, Hunters, Ironworkers, Miners, Verderers, Woodsmen

Town & Country: High Weald

Wales

Harlech Castle, Wales .. Wales .. Wales .. Wales - Medieval ..

- Tissø, Ribe ..

Wales .. Wales .. Wales - Medieval ..

London - Tudor

Medieval towns, villages

New Forest

Tamar Valley, Cornwall ..

Town & Country: Agisters, Archaeology, Forests, History, Hunters, Ironworkers, Miners, Verderers, Woodsmen

Town & Country: High Weald

Wales

Harlech Castle, Wales .. Wales .. Wales .. Wales - Medieval ..

Destruction

Mapping

Abingdon

Bath Abbey Photogrammetry

Labels:

11thC,

14thC,

1st millennium,

Anglo-Saxons,

archeology,

construction,

Dark Ages,

medieval,

Normans,

religion,

Roman,

skill,

stone

Berkeley

Berkeley was first recorded in 824 as Berclea, from the Old English for "birch lea".

Berkeley was a significant place in medieval times. It was a port and market-town, and the meeting place of the hundred of Berkeley. After the Norman Conquest, a Flemish noble named Roger de Tosny was appointed Provost of the manor of Berkeley by his brother-in-law (or perhaps uncle) Earl William FitzOsbern. His family took the name "de Berkeley", and it was he who began the construction of Berkeley Castle, which was completed by his son, also Roger. A younger son of the elder Roger, John de Berkeley, went north to Scotland with Queen Maud, becoming the progenitor of the Scottish Barclay family.

The parish of Berkeley was the largest in Gloucestershire. It included the tithings of Alkington, Breadstone, Ham, Hamfellow and Hinton, and the chapelry of Stone, which became a separate parish in 1797.

Berkeley lies midway between Bristol and Gloucester, on a small hill in the Vale of Berkeley. The town is on the Little Avon River, which flows into the Severn at Berkeley Pill. The Little Avon was tidal, and so navigable, for some distance inland (as far as Berkeley itself and the Sea Mills at Ham) until a 'tidal reservoir' was implemented at Berkeley Pill in the late 1960s.

https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Berkeley%2C+Gloucestershire

Berkeley is linked to the River Severn by the Little River Avon that was navigable by small barges. There was a wharf at Berkeley Pill, located near the castle. This permitted local cross-river trade with the Forest of Dean, allowing the transport of coal from its mines to Berkeley.

Berkeley is a small market town in Gloucestershire, situated in the Severn Vale, 18 miles (30km) north of Bristol. The town is located about 1.5 miles (2.4km) to the south of the River Seven. It is dominated by Berkeley Castle, home of the Fitzhardinge family. The plan of the town has changed little since medieval times, with four main streets: Canonbury Street, High Street, Salter Street and Marybrook Street (previously named Maryport Street), first mentioned in 1492, 1575, 1575 and 1516 respectively. Overshadowed in wealth and prosperity by the nearby wool and cloth producing towns of the Cotswolds and Cotswold scarp, Berkeley was nevertheless important as a local market, trading centre and as the home of the Fitzhardinge family.

http://humanities.uwe.ac.uk/bhr/Main/Berkeley/sources.htm .

Berkeley was a significant place in medieval times. It was a port and market-town, and the meeting place of the hundred of Berkeley. After the Norman Conquest, a Flemish noble named Roger de Tosny was appointed Provost of the manor of Berkeley by his brother-in-law (or perhaps uncle) Earl William FitzOsbern. His family took the name "de Berkeley", and it was he who began the construction of Berkeley Castle, which was completed by his son, also Roger. A younger son of the elder Roger, John de Berkeley, went north to Scotland with Queen Maud, becoming the progenitor of the Scottish Barclay family.

The parish of Berkeley was the largest in Gloucestershire. It included the tithings of Alkington, Breadstone, Ham, Hamfellow and Hinton, and the chapelry of Stone, which became a separate parish in 1797.

Berkeley lies midway between Bristol and Gloucester, on a small hill in the Vale of Berkeley. The town is on the Little Avon River, which flows into the Severn at Berkeley Pill. The Little Avon was tidal, and so navigable, for some distance inland (as far as Berkeley itself and the Sea Mills at Ham) until a 'tidal reservoir' was implemented at Berkeley Pill in the late 1960s.

https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Berkeley%2C+Gloucestershire

Berkeley is linked to the River Severn by the Little River Avon that was navigable by small barges. There was a wharf at Berkeley Pill, located near the castle. This permitted local cross-river trade with the Forest of Dean, allowing the transport of coal from its mines to Berkeley.

Berkeley is a small market town in Gloucestershire, situated in the Severn Vale, 18 miles (30km) north of Bristol. The town is located about 1.5 miles (2.4km) to the south of the River Seven. It is dominated by Berkeley Castle, home of the Fitzhardinge family. The plan of the town has changed little since medieval times, with four main streets: Canonbury Street, High Street, Salter Street and Marybrook Street (previously named Maryport Street), first mentioned in 1492, 1575, 1575 and 1516 respectively. Overshadowed in wealth and prosperity by the nearby wool and cloth producing towns of the Cotswolds and Cotswold scarp, Berkeley was nevertheless important as a local market, trading centre and as the home of the Fitzhardinge family.

http://humanities.uwe.ac.uk/bhr/Main/Berkeley/sources.htm .

Birmingham 1300

Exploring Medieval Birmingham 1300

https://sarahhayes.org/tag/british-history/page/2/

This 'virtual' tour is based on a model interactive of medieval Birmingham, now on display in the exhibition 'Birmingham: its people, its history' at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Discover Birmingham's medieval past by taking a tour through the heart of the 14th century town.

https://sarahhayes.org/tag/british-history/page/2/

This 'virtual' tour is based on a model interactive of medieval Birmingham, now on display in the exhibition 'Birmingham: its people, its history' at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Discover Birmingham's medieval past by taking a tour through the heart of the 14th century town.

Birmingham ~ 1300 > .

Medieval construction techniques - barn, castle, longhouse, town

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6Hg-KpTzAhRPje77jb5Y0kn

Birmingham - medieval streets

http://www.birminghamconservationtrust.org/volunteering-with-bct/blogger-profiles/exploring-birminghams-medieval-streets/

The medieval village of Birmingham was developed by its Norman lords into a successful market town. The area's agricultural trade became concentrated on the town and this encouraged the development of agriculture-related industries. At the beginning of this period settlements were scattered and villages were tiny if indeed they yet existed. As time went on the area developed with a mixture of individual farmsteads typical of a wooded area with room for expansion and open strip fields which were worked in common. Documentary evidence exists for a large number of farms and watermills many of which continued until the 19th century.

Birmingham Manor House in Moat Lane is known to have been occupied by the de Bermingham family from at least the 12th century. Its moat was circular which confirms a 12th century date. Observations during the 1960s Bull Ring development and road construction in 2000 prior to the building of the new Bull Ring centre suggest that a stone manor house stood within the moat with a range of outbuildings. The manor house was rebuilt in the 13th century, again in stone. The de Berminghams owned the manor until 1536 and were the longest surviving Norman lords in the area. However, when Edward de Bermingham died in 1538, the manor reverted to the Crown.

....

The first Bull Ring development was certainly the work of Peter de Birmingham. Peter had inherited a manor with little agricultural potential. Both before and after the Norman Conquest of 1066, the manor had been valued at only 20 shillings, one of the poorer manors in the area. Neigbouring Aston was worth four times as much. The manor was fairly small with little woodland and consisted of a substantial area of unproductive heathland (See Birmingham Heath below.).

From William [FitzAnsculf of Dudley Castle} Richard [presumably Richard de Birmingham] holds 4 hides in Birmingham. Land for 6 ploughteams. In the demesne [the lord's own land]1 hide. 5 villeins & 4 bordars with 2 ploughteams. Woodland half a league long & 2 furlongs [wide]. The value was and is 20 shillings. Wulfwin [Richard's Anglo-Saxon predecessor] held it freely in the time of King Edward.

In 1166 the lord of the manor, Peter de Birmingham bought from King Henry II the right to hold a market every Thursday at his 'castle'. It may well be that an informal market already took place outside St Martin's Church and that Peter was capitalising on this. Under the charter, outsiders had to pay tolls to come into the market; Birmingham townspeople did not. Merchants and traders were thus encouraged to live in Birmingham town and so pay a rent to the lord at a rate many times greater than an agricultural rent would have produced. All over England medieval lords set up markets, but Peter's, probably because it was the earliest in Warwickshire and on the Birmingham plateau, was the most successful.

The charter was confirmed by Richard I in 1189 for Peter's son William at his town, not at his castle, of Birmingham. It is likely that Peter or William had laid Birmingham out as a new town with building plots for rent. This was probably the first time that there was a 'proper' village round a village green, the Bull Ring, where the market took place.

The buildings of the medieval town spread from Digbeth and Deritend up the hill to the Bull Ring and along the High Street. There was additional building from the Bull Ring along Edgbaston Street. From a Domesday population of some 50 people in the manor, by 1300 the town had a population of perhaps 1500 people. However, as a result of the Black Death c1350, this may have been cut this to 750 or to as low as 500. It was to be another 200 years before the population was to reach that figure again.

Very little documentary evidence survives of medieval Birmingham. Not a single document is known to have survived between the 1086 Domesday Book and the 1166 Market Charter and very little survives from the Middle Ages.

........

Within a hundred years of the Market Charter Birmingham grew from a small farming village into a thriving town which attracted merchants, craftsmen, manufacturers and many local immigrants. Surviving records from other markets nearby show the sort of trading that went on. Vegetables and corn, sheep and cattle and horses were sold, as well as coal, salt, millstones and various metals. People could buy a wide range of goods, including some from abroad: aniseed, almonds, basketry, iron goods, liquorice, oranges, pomegranates, pottery, prunes, silk, spices, tinware, white paper, white soap and wine.

Birmingham merchants are known to have traded regularly with London and with the major ports of Kings Lynn and Bristol. Records show that they sold cloth made from local wool, fulled, dyed and woven locally, as well as locally produced leather and leather goods and small metal goods. During excavations prior to the building of the new Bull Ring in 2003, evidence of a number of industries was found, some of it relating to agriculture as would be expected in a small market town, but also a much wider range including the manufacture of buttons, flax and hemp, glass, leather, pottery and metal working. Birmingham was well behind Coventry in woollen cloth production. Coventry market handled 95% of Warwickshire cloth. Birmingham, although second in turnover, handled only 1.5%. Nonetheless, cloth making and selling was important to the town. Other trades also centred on the market, making and selling agricultural equipment of wood or iron, or processing agricultural products, and leather goods.

Although the farmland of the manor of Birmingham was not particularly good, tenants in all manors owed labour service to their lord on the demesne, which entailed carrying out farmwork on the lord's own land. As people moved to Birmingham for the market trade, some tenants grew rich enough to pay cash for the lord to employ labour rather than use their own labour or they paid for labourers to carry out their dues. The town increasingly became less a farming village and increasingly dependent on its market trade and associated industries. In 1226 amongst individuals paying cash instead of doing the hay-making themselves were merchants, weavers, a tailor and a smith.

Fairs were important occasions both commercially and socially. They drew large numbers of people from the local area as well as from further afield and enabled commerce to be conducted between merchants. In 1250 Henry III granted to William de Bermingham the right to hold a four-day fair starting on the eve of Ascension Day (Ascension is 40 days after Easter.). And in 1251 permission was also given to hold a two-day fair beginning on the eve of the Feast of St John the Baptist, 24 June. The dates were later found to be too close together and by 1752 the fairs had been moved to Michaelmas, 29 September, when people were in town to pay their half-yearly, and to Whit Tuesday, seven weeks after Easter.

It is not known whether there was an early church on the site of St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring. As the town grew richer during the 12th century, either the church was built or rebuilt by the de Birminghams, and other rich local people in keeping with its place at the centre of a thriving market town. Nothing now remains of the 12th-century building except for the foundations of the tower, some internal stonework in the tower and the tombs of some of the medieval lords: Sir William de Birmingham c1325 the five diagonal lozenges of whose shield form part of the City's arms, Sir Fulk de Birmingham c1350 and Sir John de Birmingham c1380.

The oldest document relating to Birmingham held in Birmingham Reference Library records the conveyance of land in the foreign of Birmingham from Robert, son of John Philip of Birmingham to John Stodleye, burgess of Birmingham. The foreign was the agricultural part of the manor outside the borough, outside the specified area reserved for housing and trade. A burgess was one who paid rent in the borough and had certain privileges, primarily those of not paying market tolls and freedom from labour obligations to the lord of the manor. Town rents were generally up to 40 times more expensive than agricultural rents; thus a thriving market town was very profitable for a manorial lord. This is further evidence of Birmingham's status as a town and no longer a village.

The Augustinian Priory Hospital of St Thomas the Apostle was a monastery endowed by wealthy Birmingham merchants before 1286. It had extensive lands in Birmingham, Aston and Saltley whose rents helped pay for the care of the poor and the sick. This priory, along with thousands of others across the country, was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1536. The buildings were demolished and the lands sold off. The Minories is on the site of the Priory buildings, Old Square stands on the site of the Priory Close and Corporation Street is built over the graveyard. During the construction of the houses in Old Square in 1696 the cellars were said to have shown evidence of the Priory's foundations. Birmingham's first historian, William Hutton rescued a fragment of moulded masonry which may now be seen in Birmingham Museum. The streetnames, Upper Priory and Lower Priory survive as Priory Queensway to the present. The western side of the priory estate was the prior's coneygre ie. 'rabbit warren'. Rabbits were introduced by the Normans from the Mediterranean during the 12th century. At that time they were only half-hardy animals and mounds of soft earth had to be dug to allow them to make burrows. Their meat and fur were luxury items. By the 1300s there were many warrens and rabbits were an established species providing a ready and cheaply maintained supply of meat throughout the year. The warren, in the area around the Town Hall and Central Library, gave a former name to Colmore Row and Steelhouse Lane which was known as Priors Conyngre Lane until the 19th century.

The Order of the Knights Templar was a Christian military order whose international power and wealth threatened especially the interests of the French King. He had the Pope persecute and ban the Order in 1312. The Master of the Order was imprisoned in London and had brought from his wardrobe personal property amongst which were pecie de Birmingham, ie. Birmingham pieces, 22 items valued at 98 shillings. A gold clasp (not from Birmingham) was listed as worth 5 shillings. It is not known what the pieces were; they were obviously valuable and small enough to be taken easily into prison. Possibly they were gold or silver eating or drinking vessels or jewellery. The important point is that the term 'Birmingham pieces' is not explained: it must have been well known to people in London. Already at this time Birmingham may have been famous for precious metalworking or jewellery.

Fires in the timber-framed houses in medieval towns were not uncommon. The larger the town, the closer the houses and the greater the danger of fire spreading. Indeed some historians use the fact of a 'great fire' as evidence that a settlement had developed from a village into a town. In 1313 Thomas de Turkebi claimed in a Halesowen court case that all his documents had been burned ad magnam combustionem ville de Birmingham, 'in the great fire of the town of Birmingham'. As the evidence was accepted without question, it is clear that Birmingham was a town of some size and that the Great Fire of Birmingham locally a well known event. In 1327, the year in which Sir William de Birmingham was summoned to Parliament, the Lay Subsidy Rolls, a tax on movable goods, show that Birmingham had become the third biggest town in Warwickshire, still well behind Coventry, but now overtaking the county town of Warwick.

The Guild of the Holy Cross was founded in 1392 by wealthy merchants who set up almshouses for the poor, paid for the town midwife and two priests at St Martin's Church, maintained a chiming clock at the Guild Hall in New Street and were responsible for the upkeep of some roads in the town. Most importantly for the town's economy they maintained the River Rea bridges at Deritend, a major route into the town. Wealthier townspeople were now beginning to take over some of the responsibilities of the absentee lord of the manor and to govern themselves. As a religious guild, the Holy Cross was abolished by Henry VIII in 1547 and the Guild Hall became King Edward VI Grammar School.

The town grew in larger and wealthier throughout the Middle Ages and first appeared on a map, known after a later owner as Gough's Map and dating from c1360. It is represented by a picture of a house, a symbol for the smallest towns shown on the map.

https://billdargue.jimdo.com/glossary-brief-histories/a-brief-history-of-birmingham/medieval-birmingham/

https://www.google.ca/search?q=medieval+birmingham&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjtydfErrrXAhXD5lQKHZWTCB0Q_AUICigB&biw=1680&bih=895

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrYzzr8yja6Hg-KpTzAhRPje77jb5Y0kn

Birmingham - medieval streets

http://www.birminghamconservationtrust.org/volunteering-with-bct/blogger-profiles/exploring-birminghams-medieval-streets/

The medieval village of Birmingham was developed by its Norman lords into a successful market town. The area's agricultural trade became concentrated on the town and this encouraged the development of agriculture-related industries. At the beginning of this period settlements were scattered and villages were tiny if indeed they yet existed. As time went on the area developed with a mixture of individual farmsteads typical of a wooded area with room for expansion and open strip fields which were worked in common. Documentary evidence exists for a large number of farms and watermills many of which continued until the 19th century.

Birmingham Manor House in Moat Lane is known to have been occupied by the de Bermingham family from at least the 12th century. Its moat was circular which confirms a 12th century date. Observations during the 1960s Bull Ring development and road construction in 2000 prior to the building of the new Bull Ring centre suggest that a stone manor house stood within the moat with a range of outbuildings. The manor house was rebuilt in the 13th century, again in stone. The de Berminghams owned the manor until 1536 and were the longest surviving Norman lords in the area. However, when Edward de Bermingham died in 1538, the manor reverted to the Crown.

....

The first Bull Ring development was certainly the work of Peter de Birmingham. Peter had inherited a manor with little agricultural potential. Both before and after the Norman Conquest of 1066, the manor had been valued at only 20 shillings, one of the poorer manors in the area. Neigbouring Aston was worth four times as much. The manor was fairly small with little woodland and consisted of a substantial area of unproductive heathland (See Birmingham Heath below.).

From William [FitzAnsculf of Dudley Castle} Richard [presumably Richard de Birmingham] holds 4 hides in Birmingham. Land for 6 ploughteams. In the demesne [the lord's own land]1 hide. 5 villeins & 4 bordars with 2 ploughteams. Woodland half a league long & 2 furlongs [wide]. The value was and is 20 shillings. Wulfwin [Richard's Anglo-Saxon predecessor] held it freely in the time of King Edward.

In 1166 the lord of the manor, Peter de Birmingham bought from King Henry II the right to hold a market every Thursday at his 'castle'. It may well be that an informal market already took place outside St Martin's Church and that Peter was capitalising on this. Under the charter, outsiders had to pay tolls to come into the market; Birmingham townspeople did not. Merchants and traders were thus encouraged to live in Birmingham town and so pay a rent to the lord at a rate many times greater than an agricultural rent would have produced. All over England medieval lords set up markets, but Peter's, probably because it was the earliest in Warwickshire and on the Birmingham plateau, was the most successful.

The charter was confirmed by Richard I in 1189 for Peter's son William at his town, not at his castle, of Birmingham. It is likely that Peter or William had laid Birmingham out as a new town with building plots for rent. This was probably the first time that there was a 'proper' village round a village green, the Bull Ring, where the market took place.

The buildings of the medieval town spread from Digbeth and Deritend up the hill to the Bull Ring and along the High Street. There was additional building from the Bull Ring along Edgbaston Street. From a Domesday population of some 50 people in the manor, by 1300 the town had a population of perhaps 1500 people. However, as a result of the Black Death c1350, this may have been cut this to 750 or to as low as 500. It was to be another 200 years before the population was to reach that figure again.

Very little documentary evidence survives of medieval Birmingham. Not a single document is known to have survived between the 1086 Domesday Book and the 1166 Market Charter and very little survives from the Middle Ages.

........

Within a hundred years of the Market Charter Birmingham grew from a small farming village into a thriving town which attracted merchants, craftsmen, manufacturers and many local immigrants. Surviving records from other markets nearby show the sort of trading that went on. Vegetables and corn, sheep and cattle and horses were sold, as well as coal, salt, millstones and various metals. People could buy a wide range of goods, including some from abroad: aniseed, almonds, basketry, iron goods, liquorice, oranges, pomegranates, pottery, prunes, silk, spices, tinware, white paper, white soap and wine.

Birmingham merchants are known to have traded regularly with London and with the major ports of Kings Lynn and Bristol. Records show that they sold cloth made from local wool, fulled, dyed and woven locally, as well as locally produced leather and leather goods and small metal goods. During excavations prior to the building of the new Bull Ring in 2003, evidence of a number of industries was found, some of it relating to agriculture as would be expected in a small market town, but also a much wider range including the manufacture of buttons, flax and hemp, glass, leather, pottery and metal working. Birmingham was well behind Coventry in woollen cloth production. Coventry market handled 95% of Warwickshire cloth. Birmingham, although second in turnover, handled only 1.5%. Nonetheless, cloth making and selling was important to the town. Other trades also centred on the market, making and selling agricultural equipment of wood or iron, or processing agricultural products, and leather goods.

Although the farmland of the manor of Birmingham was not particularly good, tenants in all manors owed labour service to their lord on the demesne, which entailed carrying out farmwork on the lord's own land. As people moved to Birmingham for the market trade, some tenants grew rich enough to pay cash for the lord to employ labour rather than use their own labour or they paid for labourers to carry out their dues. The town increasingly became less a farming village and increasingly dependent on its market trade and associated industries. In 1226 amongst individuals paying cash instead of doing the hay-making themselves were merchants, weavers, a tailor and a smith.

Fairs were important occasions both commercially and socially. They drew large numbers of people from the local area as well as from further afield and enabled commerce to be conducted between merchants. In 1250 Henry III granted to William de Bermingham the right to hold a four-day fair starting on the eve of Ascension Day (Ascension is 40 days after Easter.). And in 1251 permission was also given to hold a two-day fair beginning on the eve of the Feast of St John the Baptist, 24 June. The dates were later found to be too close together and by 1752 the fairs had been moved to Michaelmas, 29 September, when people were in town to pay their half-yearly, and to Whit Tuesday, seven weeks after Easter.

It is not known whether there was an early church on the site of St Martin's-in-the-Bull Ring. As the town grew richer during the 12th century, either the church was built or rebuilt by the de Birminghams, and other rich local people in keeping with its place at the centre of a thriving market town. Nothing now remains of the 12th-century building except for the foundations of the tower, some internal stonework in the tower and the tombs of some of the medieval lords: Sir William de Birmingham c1325 the five diagonal lozenges of whose shield form part of the City's arms, Sir Fulk de Birmingham c1350 and Sir John de Birmingham c1380.

The oldest document relating to Birmingham held in Birmingham Reference Library records the conveyance of land in the foreign of Birmingham from Robert, son of John Philip of Birmingham to John Stodleye, burgess of Birmingham. The foreign was the agricultural part of the manor outside the borough, outside the specified area reserved for housing and trade. A burgess was one who paid rent in the borough and had certain privileges, primarily those of not paying market tolls and freedom from labour obligations to the lord of the manor. Town rents were generally up to 40 times more expensive than agricultural rents; thus a thriving market town was very profitable for a manorial lord. This is further evidence of Birmingham's status as a town and no longer a village.

The Augustinian Priory Hospital of St Thomas the Apostle was a monastery endowed by wealthy Birmingham merchants before 1286. It had extensive lands in Birmingham, Aston and Saltley whose rents helped pay for the care of the poor and the sick. This priory, along with thousands of others across the country, was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1536. The buildings were demolished and the lands sold off. The Minories is on the site of the Priory buildings, Old Square stands on the site of the Priory Close and Corporation Street is built over the graveyard. During the construction of the houses in Old Square in 1696 the cellars were said to have shown evidence of the Priory's foundations. Birmingham's first historian, William Hutton rescued a fragment of moulded masonry which may now be seen in Birmingham Museum. The streetnames, Upper Priory and Lower Priory survive as Priory Queensway to the present. The western side of the priory estate was the prior's coneygre ie. 'rabbit warren'. Rabbits were introduced by the Normans from the Mediterranean during the 12th century. At that time they were only half-hardy animals and mounds of soft earth had to be dug to allow them to make burrows. Their meat and fur were luxury items. By the 1300s there were many warrens and rabbits were an established species providing a ready and cheaply maintained supply of meat throughout the year. The warren, in the area around the Town Hall and Central Library, gave a former name to Colmore Row and Steelhouse Lane which was known as Priors Conyngre Lane until the 19th century.

The Order of the Knights Templar was a Christian military order whose international power and wealth threatened especially the interests of the French King. He had the Pope persecute and ban the Order in 1312. The Master of the Order was imprisoned in London and had brought from his wardrobe personal property amongst which were pecie de Birmingham, ie. Birmingham pieces, 22 items valued at 98 shillings. A gold clasp (not from Birmingham) was listed as worth 5 shillings. It is not known what the pieces were; they were obviously valuable and small enough to be taken easily into prison. Possibly they were gold or silver eating or drinking vessels or jewellery. The important point is that the term 'Birmingham pieces' is not explained: it must have been well known to people in London. Already at this time Birmingham may have been famous for precious metalworking or jewellery.

Fires in the timber-framed houses in medieval towns were not uncommon. The larger the town, the closer the houses and the greater the danger of fire spreading. Indeed some historians use the fact of a 'great fire' as evidence that a settlement had developed from a village into a town. In 1313 Thomas de Turkebi claimed in a Halesowen court case that all his documents had been burned ad magnam combustionem ville de Birmingham, 'in the great fire of the town of Birmingham'. As the evidence was accepted without question, it is clear that Birmingham was a town of some size and that the Great Fire of Birmingham locally a well known event. In 1327, the year in which Sir William de Birmingham was summoned to Parliament, the Lay Subsidy Rolls, a tax on movable goods, show that Birmingham had become the third biggest town in Warwickshire, still well behind Coventry, but now overtaking the county town of Warwick.

The Guild of the Holy Cross was founded in 1392 by wealthy merchants who set up almshouses for the poor, paid for the town midwife and two priests at St Martin's Church, maintained a chiming clock at the Guild Hall in New Street and were responsible for the upkeep of some roads in the town. Most importantly for the town's economy they maintained the River Rea bridges at Deritend, a major route into the town. Wealthier townspeople were now beginning to take over some of the responsibilities of the absentee lord of the manor and to govern themselves. As a religious guild, the Holy Cross was abolished by Henry VIII in 1547 and the Guild Hall became King Edward VI Grammar School.

The town grew in larger and wealthier throughout the Middle Ages and first appeared on a map, known after a later owner as Gough's Map and dating from c1360. It is represented by a picture of a house, a symbol for the smallest towns shown on the map.

https://billdargue.jimdo.com/glossary-brief-histories/a-brief-history-of-birmingham/medieval-birmingham/

https://www.google.ca/search?q=medieval+birmingham&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjtydfErrrXAhXD5lQKHZWTCB0Q_AUICigB&biw=1680&bih=895

Bristol

Bristol, River Avon tide

https://www.youtube.com/user/brazenforce/videos

Bristol

http://www.historictownsatlas.org.uk/atlas/volume-ii/atlas-historic-towns-volume-2/bristol

http://www.historictownsatlas.org.uk/sites/historictownsatlas/files/atlas/town/bristol_2_late_12th__13th_centuries.pdf

http://www.historictownsatlas.org.uk/sites/historictownsatlas/files/atlas/town/bristol_3_14th_century.pdf

https://www.reddit.com/r/history/comments/61fdp6/heres_a_collection_of_over_360_historical_city/

https://www.youtube.com/user/brazenforce/videos

Bristol

http://www.historictownsatlas.org.uk/atlas/volume-ii/atlas-historic-towns-volume-2/bristol

http://www.historictownsatlas.org.uk/sites/historictownsatlas/files/atlas/town/bristol_2_late_12th__13th_centuries.pdf

http://www.historictownsatlas.org.uk/sites/historictownsatlas/files/atlas/town/bristol_3_14th_century.pdf

https://www.reddit.com/r/history/comments/61fdp6/heres_a_collection_of_over_360_historical_city/

Caerllion & Caerwent - Isca Augusta & Venta Silurum

Wales is the Place to See Amazing Roman Forts > .

Wales is home to one of the most perfectly-preserved Roman fortifications in all of northern Europe. In Caerwent, near the southern city of Newport, sections of the original first century Roman wall still remain.

During the Middle Ages, Caerleon or nearby Venta Silurum (now Caerwent) was the administrative centre of the Kingdom of Gwent. The parish church, St Cadoc's was founded on the site of the legionary headquarters building probably sometime in the 6th century. A Norman-style motte and bailey castle was built outside the eastern corner of the old Roman fort, possibly by the Welsh Lord of Caerleon, Caradog ap Gruffydd. The Domesday Book of 1086 recorded that a small colony of eight carucates of land (about 1.5 square miles) in the jurisdiction of Caerleon, seemingly just within the welsh Lordship of Gwynllwg, was held by Turstin FitzRolf, standard bearer to William the Conqueror at Hastings, subject to William d'Ecouis, a magnate of unknown antecedents with lands in Hereford, Norfolk and other counties. Also listed on the manor were three Welshmen with as many ploughs and carucates, who continued their Welsh customs (leges Walensi viventes). Caerleon itself may have remained in welsh hands, or may have changed hands frequently.

From the apparent banishment of Turstin by William II, Turstin's lands were transferred in 1088 by Wynebald de Ballon, brother of Hamelin de Ballon who held Abergavenny further up the River Usk. At about the same time as Wynebald's lands may have passed via his daughter to Henry Newmarch, possible illegitimate son of Bernard de Newmarch, c. 1155 the Welsh Lord of Caerleon, Morgan ab Owain, grandson of King Caradog ap Gruffudd, was recognized by Henry II. Subsequently Caerleon continued in Welsh hands, subject to occasional battles with the Normans. Caerleon was an important market and port and possibly became a borough by 1171, although no independent charters exist. In 1171 Iorwerth ab Owain and his two sons destroyed the town of Caerleon and burned the Castle. Both castle and borough were seized by William Marshal from Morgan ap Hywel in 1217 and Caerleon castle was rebuilt in stone. The remains of many of the old Roman buildings stood to some height until this time and were probably demolished for their building materials.

During the Welsh Revolt in 1402 Rhys Gethin, General for Owain Glyndŵr, took Caerleon Castle together with those of Newport, Cardiff, Llandaff, Abergavenny, Caerphilly and Usk by force. This was probably the last time Caerleon castle was ruined, though the walls were still standing in 1537 and the castle ruins only finally collapsed in 1739 - their most obvious remnant is the Round Tower at the Hanbury Arms public house. The Tower is a Grade II* listed building.

Cas-gwent

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chepstow

Chester, Cheshire

A Walk Through Chester, England

Beeston Castle (Cheshire) is one of the most dramatic ruins in the English landscape. Built by Ranulf, 6th Earl of Chester, in the 1220s, the castle incorporates the banks and ditches of an Iron Age hillfort. Henry III seized the castle in 1237 and it remained in royal ownership until the 16th century. In the Civil War it withstood a long siege in 1644–5, before being surrendered by the Royalists and partially demolished.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HIEX0p8GQJI

http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/beeston-castle-and-woodland-park/history/

53.12905, -2.69066

Cosmeston Medieval Village (Wales)

Gloucester, Berkeley Castle, Edward II | Longbow, bodkin arrows | Newport ship

Cosmeston Medieval Village is a "living history" medieval village near Lavernock in the Vale of Glamorgan not far from Penarth and Cardiff in south Wales.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSy48H2ocSc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmeston_Medieval_Village

http://www.valeofglamorgan.gov.uk/en/enjoying/Coast-and-Countryside/cosmeston-lakes-country-park/cosmeston-medieval-village/Cosmeston-Medieval-Village.aspx .

The Luttrell Psalter - A Year in a Medieval English Village > .

Cosmeston Medieval Village (Wales) is a "living history" medieval village near Lavernock in the Vale of Glamorgan not far from Penarth and Cardiff in south Wales.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSy48H2ocSc

https://youtu.be/MAhJtyM8kGI?t=18m35s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FlPu43OGSNc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmeston_Medieval_Village

http://www.valeofglamorgan.gov.uk/en/enjoying/Coast-and-Countryside/cosmeston-lakes-country-park/cosmeston-medieval-village/The-Village-Buildings.aspx

http://www.valeofglamorgan.gov.uk/en/enjoying/Coast-and-Countryside/cosmeston-lakes-country-park/cosmeston-medieval-village/Cosmeston-Medieval-Village.aspx .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSy48H2ocSc .

Cosmeston Medieval Village is a "living history" medieval village near Lavernock in the Vale of Glamorgan not far from Penarth and Cardiff in south Wales.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSy48H2ocSc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmeston_Medieval_Village

http://www.valeofglamorgan.gov.uk/en/enjoying/Coast-and-Countryside/cosmeston-lakes-country-park/cosmeston-medieval-village/Cosmeston-Medieval-Village.aspx .

The Luttrell Psalter - A Year in a Medieval English Village > .

Cosmeston Medieval Village (Wales) is a "living history" medieval village near Lavernock in the Vale of Glamorgan not far from Penarth and Cardiff in south Wales.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSy48H2ocSc

https://youtu.be/MAhJtyM8kGI?t=18m35s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FlPu43OGSNc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmeston_Medieval_Village

http://www.valeofglamorgan.gov.uk/en/enjoying/Coast-and-Countryside/cosmeston-lakes-country-park/cosmeston-medieval-village/The-Village-Buildings.aspx

http://www.valeofglamorgan.gov.uk/en/enjoying/Coast-and-Countryside/cosmeston-lakes-country-park/cosmeston-medieval-village/Cosmeston-Medieval-Village.aspx .

Cotswolds, Maps

A46 Bath Road Bike Descent into Nailsworth

Minchinhampton

https://youtu.be/ht0jbK8GZZY?t=393

Brimscombe

https://youtu.be/ht0jbK8GZZY?t=59

Midland Fishery, Nailsworth

https://youtu.be/DzIxU-0qEKA?t=454

Haresfield Beacon - Painswick - Bulls Cross #pGloc #pΜinchΝail

Stroud Circular Walk 4 - Bulls Cross to Bisley

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CkmQ3_6NV3s

Stroud Circular Walk 5 - Bisley to Toadsmoor Pools

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqqTtncusbI

Stroud Circular Walk 6 - Toadsmoor - Minchinhampton - Gatcombe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ht0jbK8GZZY

Stroud Circular Walk 7 - Gatcombe - Horsley - Nailsworth

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DzIxU-0qEKA

Nailsworth

https://youtu.be/DzIxU-0qEKA?t=892

Stroud Circular Walk 8 THE END - Nailsworth - Woodchester - Stonehouse

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_uPhkNaBj30

Stroud Stonehouse - A Year in Timelapse 2018

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AaMhWtfJf48

Minchinhampton Common - The Ladder - Nailsworth #pGloc #pΜinchΝail

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UBPpUOqA3s

Minchinhampton Common - Butterow Hill - Stroud Bowbridge

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29wWx4joqy4

Thames - Oxford to Lechlade

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xjdd5plIalw

Lechlade

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yM4Ddb1yYMk

Lower Oxford Canal to Banbury

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cbsr0hj3R1o

Back up the Oxford

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6o8UvmOQRkM

River Avon from Tewkesbury to Comberton Quay

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_Dsd00hbo8

Minchinhampton

https://youtu.be/ht0jbK8GZZY?t=393

Brimscombe

https://youtu.be/ht0jbK8GZZY?t=59

Midland Fishery, Nailsworth

https://youtu.be/DzIxU-0qEKA?t=454

Haresfield Beacon - Painswick - Bulls Cross #pGloc #pΜinchΝail

Stroud Circular Walk 4 - Bulls Cross to Bisley

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CkmQ3_6NV3s

Stroud Circular Walk 5 - Bisley to Toadsmoor Pools

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqqTtncusbI

Stroud Circular Walk 6 - Toadsmoor - Minchinhampton - Gatcombe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ht0jbK8GZZY

Stroud Circular Walk 7 - Gatcombe - Horsley - Nailsworth

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DzIxU-0qEKA

Nailsworth

https://youtu.be/DzIxU-0qEKA?t=892

Stroud Circular Walk 8 THE END - Nailsworth - Woodchester - Stonehouse

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_uPhkNaBj30

Stroud Stonehouse - A Year in Timelapse 2018

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AaMhWtfJf48

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UBPpUOqA3s

Minchinhampton Common - Butterow Hill - Stroud Bowbridge

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=29wWx4joqy4

Thames - Oxford to Lechlade

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xjdd5plIalw

Lechlade

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yM4Ddb1yYMk

Lower Oxford Canal to Banbury

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cbsr0hj3R1o

Back up the Oxford

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6o8UvmOQRkM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_Dsd00hbo8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KZ63N7J6Oc

Ross-on-Wye (Welsh: Rhosan ar Wy) is a small market town with a population of 10,700 (according to the 2011 census), in south eastern Herefordshire, England, located on the River Wye, and on the northern edge of the Forest of Dean.

The 700-year-old parish church of St. Mary's is the town's most prominent landmark and its tall pointed spire is visible when approaching the town from all directions.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ross-on-Wye

History

Most of the present church was built between about 1280 and its dedication in 1316 (blue). By the middle of the fourteenth century the east end had been extended and the tower added, together with the porches to the north and south (green and red). The Markye Chapel on the south side was attached in 1510 (purple). The present ground plan of the church was completed in the nineteenth century with the addition of the organ chamber (yellow).

The building is in the Decorated style, with slender columns and pointed arches. There are six piscinae in the church, indicating that at one time there were six altars.

The stained glass in the east window dates back to 1430, and has an unusual history. Other items of special interest include a small stained glass window above the chancel arch depicting Joseph holding the baby Jesus (an almost unique portrayal), a memorial in the chancel containing a poem written by Sir Walter Raleigh on the eve of his execution, and memorials to John Kyrle, the Man of Ross.

https://rawchurch.org.uk/ross/

Hereford Cathedral

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vegqns6THw

Tudor England

http://googlemapsmania.blogspot.com/2018/09/the-interactive-map-of-tudor-england.html

Great Fire of London 1666

http://googlemapsmania.blogspot.com/2016/09/mapping-great-fire-of-london.html

Britain

https://www.heritagedaily.com/2018/06/5-ancient-maps-of-britain/121512

https://watabou.itch.io/medieval-fantasy-city-generator

Ross-on-Wye (Welsh: Rhosan ar Wy) is a small market town with a population of 10,700 (according to the 2011 census), in south eastern Herefordshire, England, located on the River Wye, and on the northern edge of the Forest of Dean.

The 700-year-old parish church of St. Mary's is the town's most prominent landmark and its tall pointed spire is visible when approaching the town from all directions.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ross-on-Wye

History

Most of the present church was built between about 1280 and its dedication in 1316 (blue). By the middle of the fourteenth century the east end had been extended and the tower added, together with the porches to the north and south (green and red). The Markye Chapel on the south side was attached in 1510 (purple). The present ground plan of the church was completed in the nineteenth century with the addition of the organ chamber (yellow).

The building is in the Decorated style, with slender columns and pointed arches. There are six piscinae in the church, indicating that at one time there were six altars.

The stained glass in the east window dates back to 1430, and has an unusual history. Other items of special interest include a small stained glass window above the chancel arch depicting Joseph holding the baby Jesus (an almost unique portrayal), a memorial in the chancel containing a poem written by Sir Walter Raleigh on the eve of his execution, and memorials to John Kyrle, the Man of Ross.

https://rawchurch.org.uk/ross/

Hereford Cathedral

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vegqns6THw

Tudor England

http://googlemapsmania.blogspot.com/2018/09/the-interactive-map-of-tudor-england.html

Great Fire of London 1666

http://googlemapsmania.blogspot.com/2016/09/mapping-great-fire-of-london.html

Britain

https://www.heritagedaily.com/2018/06/5-ancient-maps-of-britain/121512

https://watabou.itch.io/medieval-fantasy-city-generator

Dartmoor - Ancient Road of The Dead

Devon, Buckfast Abbey, Dissolution of the Monasteries, pilgrimage,

Dunwich - Disappearing Medieval Port

.The Real Atlantis is Hiding Underneath Britain - Th2 > .

Dunwich is a village and civil parish in Suffolk, England. It is in the Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB around 92 miles (148 km) north-east of London, 9 miles (14 km) south of Southwold and 7 miles (11 km) north of Leiston, on the North Sea coast.

In the Anglo-Saxon period, Dunwich was the capital of the Kingdom of the East Angles, but the harbour and most of the town have since disappeared due to coastal erosion. At its height it was an international port similar in size to 14th-century London.[1] Its decline began in 1286 when a storm surge hit the East Anglian coast,[2] followed by a great storm in 1287 and another great storm, also in 1287, until it eventually shrank to the village it is today. Dunwich is possibly connected with the lost Anglo-Saxon placename Dommoc.

The population of the civil parish at the 2001 census was 84, which increased to 183 according to the 2011 Census, though the area used by the Office of National Statistics for 2011 also includes part of the civil parish of Westleton. There is no parish council; instead there is a parish meeting.

In the Anglo-Saxon period, Dunwich was the capital of the Kingdom of the East Angles, but the harbour and most of the town have since disappeared due to coastal erosion. At its height it was an international port similar in size to 14th-century London.[1] Its decline began in 1286 when a storm surge hit the East Anglian coast,[2] followed by a great storm in 1287 and another great storm, also in 1287, until it eventually shrank to the village it is today. Dunwich is possibly connected with the lost Anglo-Saxon placename Dommoc.

Since the 15th century, Dunwich has frequently been identified with Dommoc – the original seat of the Anglo-Saxon bishops of the Kingdom of East Anglia established by Sigeberht of East Anglia for Saint Felix in c. 629–31. Dommoc was the seat of the bishops of Dommoc until around 870, when the East Anglian kingdom was taken over by the initially pagan Danes. Years later, antiquarians would even describe Dunwich as being the "former capital of East Anglia". However, many historians now prefer to locate Dommoc at Walton Castle, which was the site of a Saxon shore fort.

The Domesday Book of 1086 describes it as possessing three churches. At that time it had an estimated population of 3,000.

On 1 January 1286, a storm surge reached the east edge of the town and destroyed buildings in it. Before that, most recorded damage to Dunwich was loss of land and damage to the harbour.

This was followed by two further surges the next year, the South England flood of February 1287 and St. Lucia's flood in December. A fierce storm in 1328 also swept away the entire village of Newton, a few miles up the coast. Another large storm in 1347 swept some 400 houses into the sea. The Grote Mandrenke around 16 January 1362 finally destroyed much of the remainder of the town.

Most of the buildings that were present in the 13th century have disappeared, including all eight churches, and Dunwich is now a small coastal village. The remains of a 13th-century Franciscan priory (Greyfriars) and the Leper Hospital of St James can still be seen. A popular local legend says that, at certain tides, church bells can still be heard from beneath the waves.

Characterizing the fate of the town as the loss of "a busy port to ... 14th century storms that swept whole parishes into the sea" is inaccurate. It appears that the port developed as a sheltered harbour where the Dunwich River entered the North Sea. Coastal processes including storms caused the river to shift its exit 2.5 miles (4 km) north to Walberswick, at the River Blyth. The town of Dunwich lost its raison d'etre and was largely abandoned. Sea defences were not maintained and coastal erosion progressively invaded the town.

As a legacy of its previous significance, the parliamentary constituency of Dunwich retained the right to send two members to Parliament until the Reform Act 1832 and was one of Britain's most notorious rotten boroughs.

By the mid-19th century, the population had dwindled to 237 inhabitants and Dunwich was described as a "decayed and disfranchised borough". A new church, St James, was built in 1832 after the abandonment of the last of the old churches, All Saints', which had been without a rector since 1755. All Saints' Church fell into the sea between 1904 and 1919, the last major portion of the tower succumbing on 12 November 1919. In 2005 historian Stuart Bacon stated that recent low tides had shown that shipbuilding had previously occurred in the town.

The Domesday Book of 1086 describes it as possessing three churches. At that time it had an estimated population of 3,000.

On 1 January 1286, a storm surge reached the east edge of the town and destroyed buildings in it. Before that, most recorded damage to Dunwich was loss of land and damage to the harbour.

This was followed by two further surges the next year, the South England flood of February 1287 and St. Lucia's flood in December. A fierce storm in 1328 also swept away the entire village of Newton, a few miles up the coast. Another large storm in 1347 swept some 400 houses into the sea. The Grote Mandrenke around 16 January 1362 finally destroyed much of the remainder of the town.

Most of the buildings that were present in the 13th century have disappeared, including all eight churches, and Dunwich is now a small coastal village. The remains of a 13th-century Franciscan priory (Greyfriars) and the Leper Hospital of St James can still be seen. A popular local legend says that, at certain tides, church bells can still be heard from beneath the waves.

Characterizing the fate of the town as the loss of "a busy port to ... 14th century storms that swept whole parishes into the sea" is inaccurate. It appears that the port developed as a sheltered harbour where the Dunwich River entered the North Sea. Coastal processes including storms caused the river to shift its exit 2.5 miles (4 km) north to Walberswick, at the River Blyth. The town of Dunwich lost its raison d'etre and was largely abandoned. Sea defences were not maintained and coastal erosion progressively invaded the town.

As a legacy of its previous significance, the parliamentary constituency of Dunwich retained the right to send two members to Parliament until the Reform Act 1832 and was one of Britain's most notorious rotten boroughs.

By the mid-19th century, the population had dwindled to 237 inhabitants and Dunwich was described as a "decayed and disfranchised borough". A new church, St James, was built in 1832 after the abandonment of the last of the old churches, All Saints', which had been without a rector since 1755. All Saints' Church fell into the sea between 1904 and 1919, the last major portion of the tower succumbing on 12 November 1919. In 2005 historian Stuart Bacon stated that recent low tides had shown that shipbuilding had previously occurred in the town.

The population of the civil parish at the 2001 census was 84, which increased to 183 according to the 2011 Census, though the area used by the Office of National Statistics for 2011 also includes part of the civil parish of Westleton. There is no parish council; instead there is a parish meeting.

Gloucester - medieval

MEDIEVAL GLOUCESTER 1066–1547

Gloucester 1066–1327

At the time of the Norman Conquest Gloucester was already well established as an urban community and had acquired many of the features that were to govern its fortunes during the next few centuries. (fn. 1) A royal borough in which 300 burgesses, possibly about half the total, held their land directly from the Crown (fn. 2) and the site of a royal palace set at the centre of a large agricultural estate, Gloucester enjoyed a close relationship with the rulers of England. It was unchallenged as the focus of shire administration and was also the trading centre for a wide region; within its county Bristol and Winchcombe were probably the only other places with urban characteristics. The industry which was to be the most significant in the next two or three centuries, the working of iron from the Forest of Dean, was already established. (fn. 3) The town's mint was among the thirteen or so main producers of coin in England. (fn. 4) It was also a religious centre with two monastic houses and possibly as many as eight churches and chapels. Its established position as a shire town, as well perhaps as its Roman origins, was reflected in the term civitas which was applied to it in the 11th and 12th centuries; (fn. 5) later, as that term became restricted to places with cathedrals, Gloucester was styled a town or borough until it was made a city by charter at the founding of Gloucester diocese in 1541. (fn. 6)

Gloucester's most obvious importance to the new rulers of England was its strategic position in relation to South Wales. The crossing of the Severn controlled by the town was rapidly secured by a castle, which was rebuilt on a more substantial scale in the early 12th century. (fn. 7) The castle was entrusted by the Norman kings to a notable family of royal servants who, as hereditary castellans and sheriffs of the county, were dominant in the history of Gloucester for a century after the Conquest. (fn. 8)

The continuing royal interest in Gloucester that its strategic importance ensured, as well as its inherent strength as a trading centre, were needed to overcome a period of disruption and depopulation in the years following the Conquest. A survey dating from between 1096 and 1101 records that of the 300 royal burgages that had existed in Edward the Confessor's reign 82 were uninhabited and another 24 had been removed to make way for the castle; half of the remainder had changed hands since the Conquest, many of the new tenants being Normans. In addition to the core of royal burgesses there were 314 who held from other landlords. The total of 508 burgesses (fn. 9) perhaps indicates a total population of about 3,000. The farm owed from the town, which had been £36 with various renders and customs in Edward the Confessor's reign and £38 4s. (presumably also with the traditional renders) in the time of Roger of Gloucester as sheriff soon after the Conquest, had been fixed at £60 by 1086; c. 1100, however, only £51 4s. appears to have been received. (fn. 10)

Domesday Book and the later survey reveal a complex pattern of landholding in the town, one that presumably dated in many of its essentials from before the Conquest. Apart from the Crown 25 other lords had burgesses c. 1100, the largest holdings being the archbishop of York's 60, held in right of St. Oswald's minster, and Gloucester Abbey's 52. The smaller estates included 6 burgesses of Samson, bishop of Exeter, apparently the remnant of a significant estate in the Southgate Street area which his predecessor Bishop Osbern had held, and the 15 burgesses of Walter of Gloucester, the hereditary sheriff and castellan. The other estates were mostly attached to outlying manors, (fn. 11) 17 of which had burgesses in Gloucester in 1086. (fn. 12) The largest holdings were attached to two important pre-Conquest estates in the neighbourhood: Deerhurst Priory, which became a possession of the abbey of St. Denis, Paris, after the Conquest, had 30 burgesses in Gloucester in 1086, while Tewkesbury manor had 8; (fn. 13) c. 1100 36 burgesses were attached to Deerhurst, while Robert FitzHamon, lord of Tewkesbury, had 22. (fn. 14) Two other manors with large holdings were Bisley with 11 burgesses in 1086 and Kempsford with 7. (fn. 15) The generally accepted explanation for such burgages attached to outlying manors, that they provided the parent manor with a foothold for conducting trade and business in the county town, is supported in the case of Gloucester. Most of the places concerned were distant Cotswold manors for which some such arrangement would be most useful; and for two of them, Quenington, which had a smith owing a cash rent and another burgess owing a rent in ploughshares, and Woodchester, which had a burgess owing a rent in iron, (fn. 16) the arrangement was a means of taking advantage of Gloucester's ironworking industry.

The century following the Norman Conquest saw major additions to Gloucester's complement of religious institutions. The survey of c. 1100 records that there were already 10 churches in Gloucester (fn. 17) and, as suggested above, most of them were probably founded before 1066. (fn. 18) Those added after the Conquest almost certainly included St. Owen's church, outside the south gate, which was probably founded by the first hereditary sheriff, Roger of Gloucester, whose son Walter added further endowments. Other late foundations were possibly the three churches with small compact parishes straddling the main market area, All Saints at the Cross and St. Mary de Grace and Holy Trinity in upper Westgate Street. The advowsons of the two last churches belonged to the Crown in the early 13th century and they were perhaps royal foundations, further manifestations of the interest shown in Gloucester by the early Norman kings. Another possibility is that they were built by wealthy townsmen, whose estates later escheated to the Crown. A total of 11 churches, all in existence by the later 12th century, exercised parochial functions in the town and its adjoining hamlets and there were also a number of non-parochial chapels. (fn. 19)

The two oldest religious houses of the town enjoyed very different fortunes after the Conquest. Under the rule of the able and energetic Abbot Serlo from 1072, Gloucester Abbey became one of the leading Benedictine houses of England. Its alienated property was recovered and additional gifts were attracted, the church was rebuilt, and the community was much enlarged. (fn. 20) The abbey's possessions in the town and immediate neighbourhood gave it a major involvement in town affairs in succeeding centuries, sometimes bringing it into conflict with the burgess community. (fn. 21) The minster of St. Oswald passed under the control of the archbishop of York and was later weakened by disputes between the archbishop and the bishop of Worcester and archbishop of Canterbury about jurisdiction. Although reconstituted c. 1150 as a priory of Augustinian canons, St. Oswald's remained a relatively poor house. (fn. 22) In wealth and property, as well as in influence in the town and locality, it was outstripped by the new Augustinian priory of Llanthony Secunda, which was established on land on the south side of the town by Miles of Gloucester in 1137. (fn. 23) Three hospitals for the sick were founded at the approaches to the town in the 12th century. The leper hospital of St. Mary Magdalen, also called the hospital of Dudstone, was established on the London road at Wotton, probably by Walter of Gloucester in the early 12th century; Roger of Gloucester, earl of Hereford, augmented the endowment in the early 1150s (fn. 24) and the hospital was subsequently controlled by the family's foundation, Llanthony Priory. (fn. 25) Another leper hospital, St. Margaret, originally St. Sepulchre, (fn. 26) had been established on a nearby site by the mid 12th century; Gloucester Abbey then controlled it (fn. 27) but in the late Middle Ages it was managed by the burgess community of Gloucester. (fn. 28) A third hospital, St. Bartholomew, at the western approach to the town, between the Foreign and Westgate bridges, was according to tradition founded in Henry II's reign in connection with a rebuilding of Westgate bridge. It was reconstituted under the rule of a prior after Henry III endowed it with St. Nicholas's church in 1229. (fn. 29)

Gloucester's varied collection of religious foundations provided objects of piety to suit all tastes and a stream of gifts of land and rents was directed towards them by the burgesses of the 12th and 13th centuries. Some burgesses preferred to endow external religious houses, and Cirencester, (fn. 30) Flaxley, (fn. 31) Winchcombe, (fn. 32) Godstow (Oxon.), (fn. 33) and Eynsham (Oxon.) (fn. 34) were among those to acquire property in the town. An alternative form of pious donation, the founding of chantries in the parish churches, had begun by the mid 13th century. (fn. 35)

Another community established in Gloucester after the Conquest was formed by the Jews, who had their quarter in Eastgate Street. (fn. 36) Jews are recorded in the town from 1168, when they were alleged to have carried out the ritual murder of a boy, (fn. 37) and a Gloucester Jew was advancing money to those going to Ireland with Strongbow's expedition in 1170. (fn. 38) A prosperous member of the community at that period was Moses le Riche, whose heir owed the Crown 300 marks in 1192 for the right to have his debts. (fn. 39) In the early years of the 13th century Gloucester Jews were financing local magnates, such as Henry de Bohun, earl of Hereford, and Roger de Berkeley, (fn. 40) , and their activities among the burgess community at the same period are revealed by sales of property to pay off debts owed to the Jews or to redeem mortgages. (fn. 41) Some 13th-century Jews acquired considerable property outside the Jewish quarter, among them Ellis of Gloucester (d. c. 1216) (fn. 42) and Jacob Coprun (d. c. 1265). (fn. 43) The Jews of Gloucester had a grant of royal protection in 1218 and were placed in the custody of 24 burgesses. (fn. 44) The Jews' chest for keeping the chirographs of debts, in the custody of a Christian and a Jew, was mentioned in 1253. (fn. 45) The tallage levied on the Jews in 1255, when those at Gloucester were assessed at 30 marks, suggests that the community was then among the 18 leading Jewries of England. (fn. 46) The Gloucester Jews were removed to Bristol in 1275 at the insistence of the lady of the borough, Queen Eleanor, who had been promised that the towns she received in dower should not contain any Jews. (fn. 47)

The proliferation of Gloucester's religious institutions and the attraction to it of a large Jewish community are among indications of the economic vitality of the town during the 12th and 13th centuries. Aids raised from the English towns during Henry II's reign suggest that Gloucester may then have ranked about ninth in order of prosperity, well behind such great regional centres as York and Norwich but among the leading county towns, on a par with such places as Oxford and Winchester. (fn. 48) No equivalent information survives at that period, however, for Bristol, the town which over succeeding centuries was to dominate the region in which Gloucester lay and exert a significant influence over its economic fortunes. When a levy of men for service overseas was made in 1212 Gloucester and Bristol both had to supply 30, (fn. 49) but an aid of 1210, when Gloucester was assessed at 500 marks and Bristol at 1,000, (fn. 50) probably provides a more accurate indication of their relative size and prosperity. Within the northern half of Gloucestershire, however, Gloucester was not seriously challenged as the trading and administrative centre. Among neighbouring settlements Tewkesbury and Cirencester became market towns soon after the Norman Conquest, but both remained much smaller than Gloucester. Of the many other places which gained markets between the late 12th and early 14th centuries several in the immediate area of Gloucester, including Newent, Cheltenham, Painswick, and Newnham, were moderately successful and made some impact on its market trade but in the expanding economic climate of the period looked to Gloucester as the centre for the supply of manufactured and imported goods.

Gloucester's trading connections with the smaller market towns of its region and its own local market area were among the diverse elements that provided its livelihood. It had an industrial base supplied in particular by ironworking, for which it was widely known at that period, and by clothmaking; it played a part in the trade of the river Severn and, mainly through Bristol, in overseas trade; and its control of the trade routes out of South Wales benefited it from before the time of the Edwardian conquest. (fn. 51) The general impression to be gained from the available information is of a steadily prospering economy, though the local financial records needed to endorse such an impression do not survive. An isolated bailiffs' account roll, for 1264–5, records the fairly substantial sum of £49 18s. 5d. produced by the tolls on trade and that at a time when the local economy was disrupted by fighting in and around Gloucester. (fn. 52)

Gloucester also benefited from its role as an administrative centre. From its castle the sheriff carried on the county government, while the town was also the venue for the justices in eyre, visiting commissions, and inquisitions of all kinds. Such events brought many people regularly to Gloucester, including inhabitants of Bristol before that town won separate county status in 1373. (fn. 53) Religious houses such as Winchcombe Abbey found it advisable to maintain lodgings for use when business brought the monks to Gloucester. (fn. 54) The town remained the site of a mint at least until the recoinage of 1248, (fn. 55) probably losing that role at a reorganization of mints in 1279. (fn. 56) Its status was also enhanced and its economy benefited by the regular visits of king and court, which continued until the mid 13th century, and by a role as a supply base during royal campaigns in Wales. Less beneficial to its economic well-being was the part its strategic position led it to play in the upheavals of the reigns of Stephen, Henry III, and Edward II. (fn. 57)

In the later 12th century the townspeople of Gloucester emerged as a community with political objectives and the wealth to acquire them from the Crown. The town secured its first charter at the beginning of Henry II's reign and in 1165 became one of the earliest places to be given the right of fee farm. An attempt soon afterwards by a group of leading burgesses to gain greater freedom from royal control was suppressed and the achievement of the right to elect bailiffs, under a charter of 1200, was the next major advance. Following that the exclusion of the county sheriff and other royal officials from interfering in their affairs remained a goal. (fn. 58) The government of the town, carried on until 1483 by the two bailiffs, acting mainly through the hundred court, settled into an oligarchical pattern; the bailiffs were drawn from a recognized class of wealthier burgesses, (fn. 59) apparently composed in the 13th century and the early 14th by the leading merchants in wine and wool and the principal wholesalers, such as mercers and drapers. (fn. 60)

Under the influence of its varied economic and administrative functions Gloucester expanded, its progress only temporarily disrupted by fires which devastated its main trading streets on several occasions in the late 12th century and the early 13th. (fn. 61) From the later 12th century suburban growth was recorded on monastic land outside the north, east, and south gates. (fn. 62) A clause in the town's charter of 1227 protecting absconded villeins who had been in the town for a year and a day from being reclaimed by their lords (fn. 63) suggests that numbers of immigrants were then being attracted to Gloucester. Surnames of 13th-century inhabitants that derived from place-names show that such immigration was mainly from a local area of north Gloucestershire villages; a few men had come from a greater distance, from Midland towns such as Ludlow, Kidderminster, Banbury, Warwick, and Northampton, and from Brecon and Abergavenny, (fn. 64) places on the main route into Wales which Gloucester commanded.

Other immigrants attracted to the town at the period were the friars: the Franciscans and Dominicans founded communities in the 1230s and the Carmelites in the 1260s. (fn. 65) The establishment of friaries in the 13th century has been seen as an index of the status of towns; Gloucester was one of 20 towns in England, but one of only 4 in the western half of the country, which attracted three or more different orders. (fn. 66)

The population of Gloucester during the period is difficult even to guess at, with the 1327 subsidy, for which 257 people were assessed, providing the first indication after the record of c. 1100. The total population in the early 14th century was perhaps around 4,000. The total sum for which Gloucester was assessed in 1327 was £28 4s. 8¼d., (fn. 67) compared with Bristol at £80 12s. and Cirencester and Tewkesbury at £13 4s. 2¼d. and £10 3s. 6d. respectively. (fn. 68) Among English towns as a whole Gloucester then ranked about 16th in order of wealth. (fn. 69)

Gloucester 1066–1327